Published Jun 27, 2023

Will the 'Real' Star Trek Please Beam Up?

Star Trek (2009) was as real as Star Trek can get.

StarTrek.com

As a child on a family trip, I sat in a hotel watching Star Trek with my cousins. One uncle grumbled to another, “I don’t like this new show. The captain never leaves the Bridge! That’s not Star Trek to me.”

Which captain irritated my uncle? Jean-Luc Picard, who left the Bridge so much that he hung out with Mark Twain, and was even captured by a Cardassian warlord! Granted, Star Trek: The Next Generation was only in its third season when my uncle made his remark, but the lesson to me was clear — complaining about Star Trek is almost as old as Star Trek itself.

It would have been no problem if my uncle simply said that he disliked The Next Generation. Everyone has their preferences, even in a franchise they love. But when he said that TNG wasn’t "real" Star Trek, my uncle went too far. Of course, TNG is real Star Trek. Its characters are, as Zefram Cochrane bluntly put it in Star Trek VIII: First Contact, "astronauts on some kind of star trek."

StarTrek.com

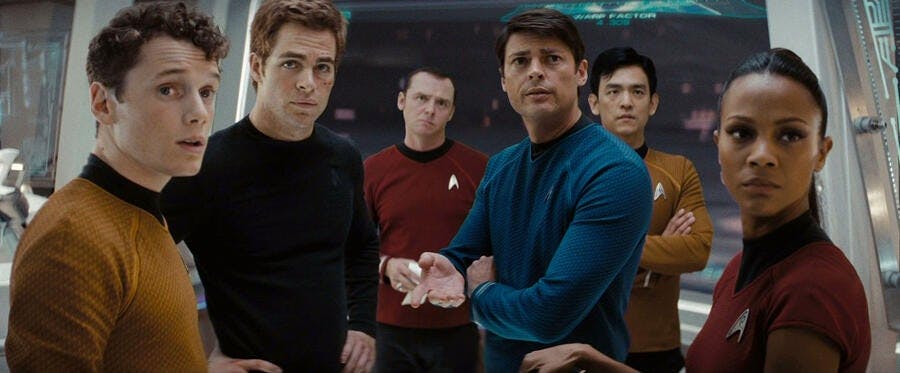

Nearly every series has been dismissed as “not real Star Trek” for some reason or another, from the station-bound stories in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine to the emotional rawness of Star Trek: Discovery. But no Star Trek franchise has received as much ire as the reboot films, starting with Star Trek (2009). Complaints started as soon as Paramount announced that Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto would replace William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy as Kirk and Spock, and they still haven’t stopped.

Although I enjoy the movie, I understand why it wouldn’t work for some. Director J.J. Abrams has little use for the diplomatic dialogues and philosophical arguments found in many Star Trek classics, preferring instead lens flares and explosions. The script from Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman contains plenty of nods to previous adventures, including an apple-munching Kirk defeating the Kobayashi Maru simulation. But the film’s plot, in which the elderly Ambassador Spock and the Romulan Nero travel to the past after the destruction of Romulus, is a different beast entirely. Once in the past, Nero begins radically altering the original timeline, starting with the destruction of the U.S.S. Kelvin and its field-commissioned Captain, George Kirk.

StarTrek.com

The movie’s critics complain that it isn’t real Star Trek because Pine and Quinto don’t play the same Kirk and Spock from The Original Series. But here’s the thing — the movie agrees! In fact, the movie is very much about the fact that the lives of the Enterprise crew are not quite right. Nero changed reality from the moment of Kirk’s birth and his actions reverberate throughout the galaxy. The characters we once knew come into being in an all-new environment, and thus make different choices.

Unmoored by the loss of his father, Kirk indulges in his reckless impulses. The cocky romantic that fans saw in an episode like “Dagger of the Mind” has been replaced by a womanizing barfly who picks fights with visiting Starfleet cadets. Spock’s reality changes when Nero destroys Vulcan and kills his mother Amanda. Once the child of two worlds, Spock now has only Earth for a home. Wishing to honor his mother’s memory, Spock embraces his human side, making for a more emotional half-Vulcan. In this new timeline, Captain Pike avoids the accident that leaves him scarred, Chekov joins the Bridge crew much earlier, and Uhura’s xenolinguistic skills earn more respect.

StarTrek.com

Because they are different people living in a different reality, these characters will not have the same adventures as the versions we saw before. They won’t be overrun with Tribbles, nor will a noble commander be their first introduction to the Romulans. For this Enterprise crew, these things never happened and they never will. But as Nero himself would put it — it happened, don’t say it didn’t happen, I saw it happen. No matter what happens in the reboot movies, all of The Original Series and movies still exist. You can watch “The City on the Edge of Forever” on the same day that you watch Star Trek (2009), which I did while prepping for this article.

StarTrek.com

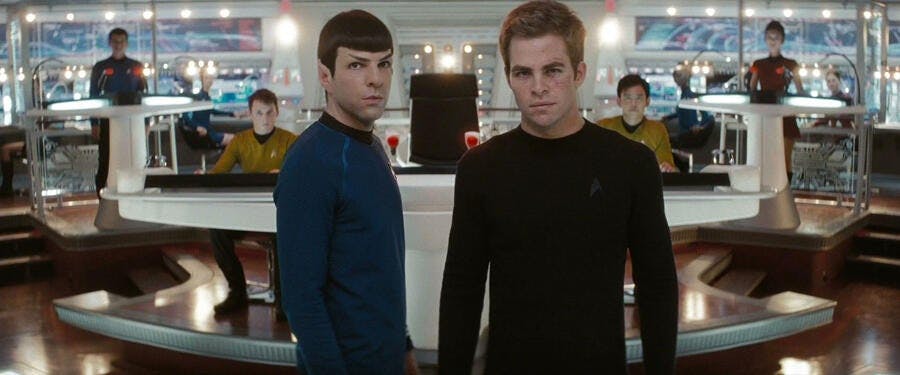

Once again, the movie makes this fact part of its plot, as illustrated in a scene that brings together the old and the new. After being marooned by Spock on an ice planet, Kirk encounters Ambassador Spock. “James T. Kirk,” Spock says to Pine’s character (with, I hasten to add, more than a little emotion in his voice). When Kirk asks how this elderly man knows who he is, Spock answers, “I have been and always shall be your friend.”

To Pine’s Kirk, Spock’s answer is bewildering and devoid of sentiment. Spock has not always been his friend; he just left Kirk to die on this planet. Nor does it make sense for the many people who first met these characters in this film. The line only gains meaning for them when Spock explains that he, even the angry and hurting version, needs Kirk as an anchor, but especially for the many of us who know these characters from earlier stories such as Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, where Spock speaks that same phrase to Kirk while sacrificing himself to save the Enterprise. Whatever the feelings between old Spock and new Kirk, my heart fills with emotion when I hear those words.

StarTrek.com

As we know from Star Trek Into Darkness, which reverses the sacrifice and leaves Kirk dead after Khan’s attack, Pine and Quinto’s characters will never say those words to each other. But Shatner and Nimoy’s characters do say them every time I re-watch The Wrath of Khan.

By bifurcating the timeline, Star Trek (2009) makes literal an aspect of Star Trek that has always been true. There can be multiple interpretations of the characters, and they are valid. Leaving aside big contradictions, like the conflicting appearances of Klingons or Trills, Star Trek has always invited differing interpretations because that’s the way interpretation works. We’re all different people, and we all bring different expectations, desires, and beliefs to a piece of fiction. No one person owns the one correct version.

StarTrek.com

In an earlier life, Nimoy’s Spock taught Shatner’s Kirk another important lesson; one drawn from Vulcan philosophy. Infinite diversity in infinite combinations has become a core part of Star Trek fandom, an essential part for celebrating the different races, genders, body types, and sexualities who contribute to the franchise’s continuing mission. It’s important to remember that infinite diversity also refers to our interpretations and experiences with these characters.

The TOS episodes my uncle loved are real Star Trek, the 90s stories I love are real Star Trek, and the 2009 film is real Star Trek because there is no one “real” Star Trek. As the 2009 film reminds us, there are infinite Treks in infinite combinations, and it’s the privilege of all fans to seek out strange new interpretations.

This article was originally published on May 5, 2021.