Published Jan 23, 2011

Trek Writer David Gerrold Looks Back - Part 1

Trek Writer David Gerrold Looks Back - Part 1

David Gerrold is very much a part of the Star Trek fabric, more so than perhaps even longtime fans may realize. Yes, he created the Tribbles, and for that alone he’s earned his place in pop culture history. But did you know that, for TOS, he wrote not only “The Trouble with Tribbles,” but also the story for “The Cloud Minders” and tapped out an un-credited rewrite of the famous “I, Mudd” episode? Or that he penned two nonfiction Trek tomes and two Trek novels? That he scripted two episodes of The Animated Seriesand even provided a voice for an episode? That he made cameo appearances inThe Motion Picture andDeep Space Nine? That he helped develop The Next Generation and served as a story editor during season one, but left after clashing with the powers that be? That he wrote and directed Blood and Fire, one of the New Voyages fan films? And then there’s his entire, award-studded non-Star Trek career as a novelist and television writer to consider. Suffice it to say there was plenty to talk about – and Gerrold had lots to say – during a recent hour-long conversation with StarTrek.com. Below is part one of our exclusive interview, and be on the lookout tomorrow for part two.

You’ve had a long and strange trip when it comes to Star Trek. When someone says the words “Star Trek” to you, do you flinch? Do you smile? What’s your relationship with the franchise these days?

Gerrold: I smile, (and) sometimes I laugh. Star Trek is a cultural landmark and only a few of us were lucky enough or privileged enough to be part of creating it. You can’t help but love the enthusiasm people have brought to it. When I see that enthusiasm I don't see a Star Trek fan, but rather somebody who’s excited by the whole idea of space exploration, getting out there and exploring the universe, and believing that we as human beings can do better. That’s what I see when I see somebody who gets excited about Star Trek. There’s an enthusiasm that goes beyond the show.

You submitted your first ideas to Gene L. Coon while you were still in college. Does it boggle your mind that this all started back when you were a student?

Gerrold: Yeah. Yes. If I hadn’t done Star Trek, I have no idea what I’d be doing these days. Star Trek kick-started my professional career. And on another level – if I ever write an autobiography, this would be something I’d touch on – it resolved all of my adolescent self-esteem issues overnight to have sold a script to Star Trek. At that time, Star Trek wasn’t this big, wonderful, magical thing. It was this second-rate TV show that only a few geeks and dorks and nerds knew about. Everyone else kind of made fun of it. We weren’t pulling great ratings. But, for me, it was like, “Guess what? I just sold a script to a primetime TV series!” I look back on it and, gosh, there was still a lot, an awful lot I had to learn about writing, but it was crossing a great big line between just being a wannabe and actually having some sense of how the system really works.

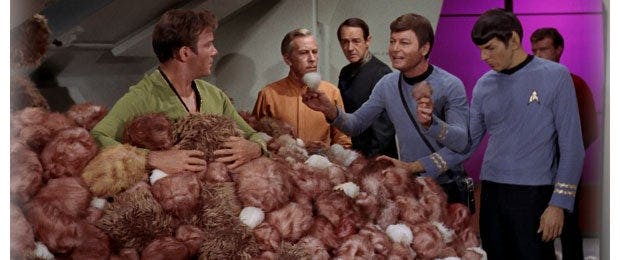

Let’s talk Tribbles. You’d originally called them Fuzzies…

Gerrold: I made the name change, and in retrospect Tribbles is a much better name because Fuzzies is too cute. I don’t think Fuzzies would have developed the same kind of cultural recognition. You wouldn't have had people referring to Fuzzies the same way they refer to Tribbles. And I think because Tribbles was a neutral word – “Here’s this nice little creature and it’s called a ‘Tribble’ – we added a word to the English language. I made a list of silly-sounding words you could call such a creature and cross off all the ones that were too silly. I wanted people to take them seriously.

If the crew had not figured out a way to nip the Tribble threat in the bud, they really could have taken over the world. Yet most people think of “The Trouble with Tribbles” as a comedy episode. Was there a part of you that thought, “Hey, guys, there’s a serious story in here and…”?

Gerrold: Oh, yeah. I wanted to do a sequel where, in order to control the Tribbles we bring in a predator from their homeworld. And the next thing that happens is that crewmen start disappearing because we have swarms of predators on the ship. But we never got around to doing that.

To this day, fans still love the episode. It’s considered one of the most popular episodes of all-time…

Gerrold: Paramount says it’s the most popular episode of all time.

Some people would argue that the best episode is “The City on the Edge of Forever…”

Gerrold: Harlan Ellison and I have an agreement. “City on the Edge of Forever” is the best episode, and “Tribbles” is the most popular.

OK, most popular. So, why? Why is “Tribbles” so popular?

Gerrold: First of all, there’s a visceral level. We like babies, kittens, puppies, white mice, panda bears, rabbits, Teddy bears. We like cute, small, fuzzy creatures. A Tribble is this creature with no face, though it’s got a mouth, right? And it purrs. So it’s the ultimate cat. Even better, it doesn't even give you the snotty look. I think it appeals to that very mammalian instinct to take care of something small and cute, like a child. In fact, I am convinced that the reason we don’t strangle our children in their beds is because they’re cute. Otherwise, they behave like little psychopaths. No, I’m kidding.

You’re credited with having written the story for “The Cloud Minders.” How do you look back on that episode?

Gerrold: That was a very frustrating experience. I know that Freddy Freiberger later believed that I had this enormous feud going on with him, but it was actually more of a disappointment in how it all turned out. He'd been given a rare opportunity, custody of one of the most ambitious and remarkable TV shows ever, and he treated it like it was just a job. I don’t think he had the same vision of Star Trek as everybody else. I came in with what I thought was a near-perfect Star Trek story, which is we find a culture that isn’t working for everybody and fix it. But my original ending was that, as they’re flying off, Kirk says, “Well, we solved another one.” Spock says, “Well, actually, it’ll take years and years and years for all of these changes to be put in place.” And McCoy says, “I wonder how many children are going to die in the meantime.” So the idea was, “Let’s get gritty. We’re not going to change things overnight, but we can put changes in place that will have long-term effects.” There was also more to the story that was about the social issue, and there was no magical zenite gas that was causing the problem. Freddy Freiberger and Margaret Armen came in and changed it to a “Let’s solve it all in the last five minutes with gas masks” (ending). And I thought, “That’s really not a very good story. It doesn’t do what Gene Roddenberry or Gene L. Coon would have been willing to do.” So I was disappointed.

You didn’t take a credit of any kind for the episode “I, Mudd.” What were you contributions to that show and why did you pass on a credit?

Gerrold: I did quite a bit of work, actually. They had actually gotten a bargain with “The Trouble with Tribbles” script and they had an extra 1,500 bucks in the budget. Gene L. Coon said, ‘Well, you know, the kid’s entitled to the 1,500 bucks he would have gotten. Let’s see what he can do on a rewrite of ‘I, Mudd.’ It doesn’t cost us anything.” That went on behind the scenes. I was not part of that conversation, but I know that happened. He called me in and said, “Read the script.” I said, “OK.” He said, “We get them all down to the planet at the end of act two. That’s halfway through the show. We really want to get them on the planet at the end of act one, at the 15-minute mark, first commercial.” He told me they’d been arguing about it for two weeks and hadn’t been able to solve this problem. I said, “Well, you can’t have the androids take Kirk’s communicator and imitate Kirk’s voice because Scotty didn’t believe it in the episode that was just re-run last night.” Gene said, “Yeah.” I said, “But you’ve demonstrated that android Norman is that strong. Well, all the androids are that strong. They just beam up to the ship, grab the crewmembers and beam them all down.”

Gene said, “Yeah, we can do that.” I said, “You don’t even need to show it. You just have one of the androids walk in and say, ‘We have completed beaming down the crew of the Enterprise.’” Gene L. Coon’s eyes went wide and he said, “My God, you’ve just done in one line of dialogue what we couldn’t do in 15 pages of script. OK, go do a rewrite on this script. Pad out and flesh this out.” So I added the 500 identical girl robots, which they thought was a funny gag and hired some twins (to realize the scene on set). I added more for the wife, Stella. They were very, very pleased. They fleshed it out a little more, but they were happy that I had given them a strong, workable structure.

So, why no screen credit?

Gerrold: Gene L. Coon said to me, “Would you like us to put this in for a script arbitration, so you can get credit and get residuals.” I said, “No. Stephen Kandel created Harry Mudd. He wrote both of these episodes and I don’t want to steal from another member of the Writers Guild. I don’t want to jump his credit. I’m a beginner. I’m learning a lot, but I’m not so greedy as to steal another writer’s residual.” Gene L. Coon again looked at me surprised. I wish more writers thought like that. In recent decades there’s been a lot less honor among writers, but that’s a whole other conversation. But I refused to take away screen credit from Stephen Kandel, whom I’ve never met. All these great writers were working for Star Trek and it was just a great honor for me to be included among that fraternity.

Over the years you’ve written a few Trek novels, including the adaptation of the TNG pilot, but we wanted to ask you about your two non-fiction books. The Trouble with Tribbles: The Birth, Sale and Final Production of One Episode was a look at pretty much everything involved in producing the TOS show of the same name, while The World of Star Trek was essentially a behind-the-scenes overview of the original show. We could ask you loads of questions, but we have lots of ground to cover and not lots of room. So let’s narrow it down to one question: When they were released in 1973, what was the reaction to the books?

Gerrold: They were very popular. My writing instructor, Irwin R. Blacker, was enormously delighted. One of the books was dedicated to him, and he sent me a very warm note saying just how impressed he was with the book. He was particularly pleased that my writing voice was so friendly and accessible. He said that I was writing like I was just sitting and having a chat with someone. Everybody in the Star Trek cast and crew thought the books were just a really nice way to honor the enthusiasm and the fun of the show. And the fans liked the books a lot, too. The books sold very well. And over and over in all the years since then, I've heard from a lot of other writers and producers that those two books had a strong influence on their own early careers, because they were the only books available then that talked about series television production. And I know that some teachers used them as textbooks for their classes, too. I think that was the best part for me.

Check back for part two of our interview tomorrow.