Published Jul 2, 2020

Watching The Next Generation in a Time of Pandemic and Uprising

The journey of the Enterprise-D remains as relevant as ever

StarTrek.com | Shutterstock/marymyyr

I was months into social distancing – a carefully calibrated, terror-inflected pattern of behavior that involved mostly staying indoors, and then staying indoors more, and then more, and then skittering out for a furtive panicked trip to the grocery store – when I decided to start watching Star Trek. It was my first time watching any of the Star Trek series, and I decided to go with The Next Generation, on the advice of a Trekkie friend. I started watching the show with a margarita’s worth of grains of salt. I was more of a swords-and-sorcery girl – I’d loved Game of Thrones, and Aragorn from Lord of the Rings was my first breathy adolescent love – and I doubted I could be as enchanted by starships and phasers. To my surprise, though, once I started, I couldn’t stop watching. I devoured all seven seasons in just over a month; it was all I wanted to do. I woke up longing for the Enterprise, and let the dulcet tones of Patrick Stewart’s voice lull me to sleep in the evening. The pandemic faded into the background; suddenly, I could traverse unknown planets from the confines of my apartment, and the walls no longer felt like they were closing in on me.

Trek is a ubiquitous cultural force, and a weighty presence in the nerdy worlds I tend to traverse, and when I thought back as to why it took me until age 30 to start watching I realized my trepidation largely came from the fact that the lore seemed too vast, and too intricate, and too closely guarded by legions of fans, to enter casually. The cultural figure of the “Trekkie” – an amalgam of the Comic Book Guy on The Simpsons and any number of satirically portrayed mouth-breathing, gimlet-eyed fanatics – felt like a major obstacle. It seemed deceptively easy to simply be able to turn on my TV and dive into a universe so vast, a matryoshka doll of nested franchises, when so many people already knew the ins and outs of Klingon philology before I’d even started.

But again, I was pleasantly surprised: when I started hesitantly sharing my first journey into the lands where no one had gone before on Twitter, I was met with a rush of gentle, welcoming enthusiasm. I’d been ready for bitter gatekeeping, or cruel dismissals of my live impressions of meeting Picard for the first time. But what I found was a rush of huge, vicarious, simple joy. Countless fans shared their recommendations for favorite episodes, their analyses of my analysis, their podcasts and YouTube videos and book recommendations from the literary canon that supplements the shows. While at times this outpouring could be overwhelming, I was struck by the gentleness at the heart of it, a genuine desire to enhance my enjoyment of something that had already brought them joy. It was a gentleness that dovetailed with the big-hearted ethos of The Next Generation itself.

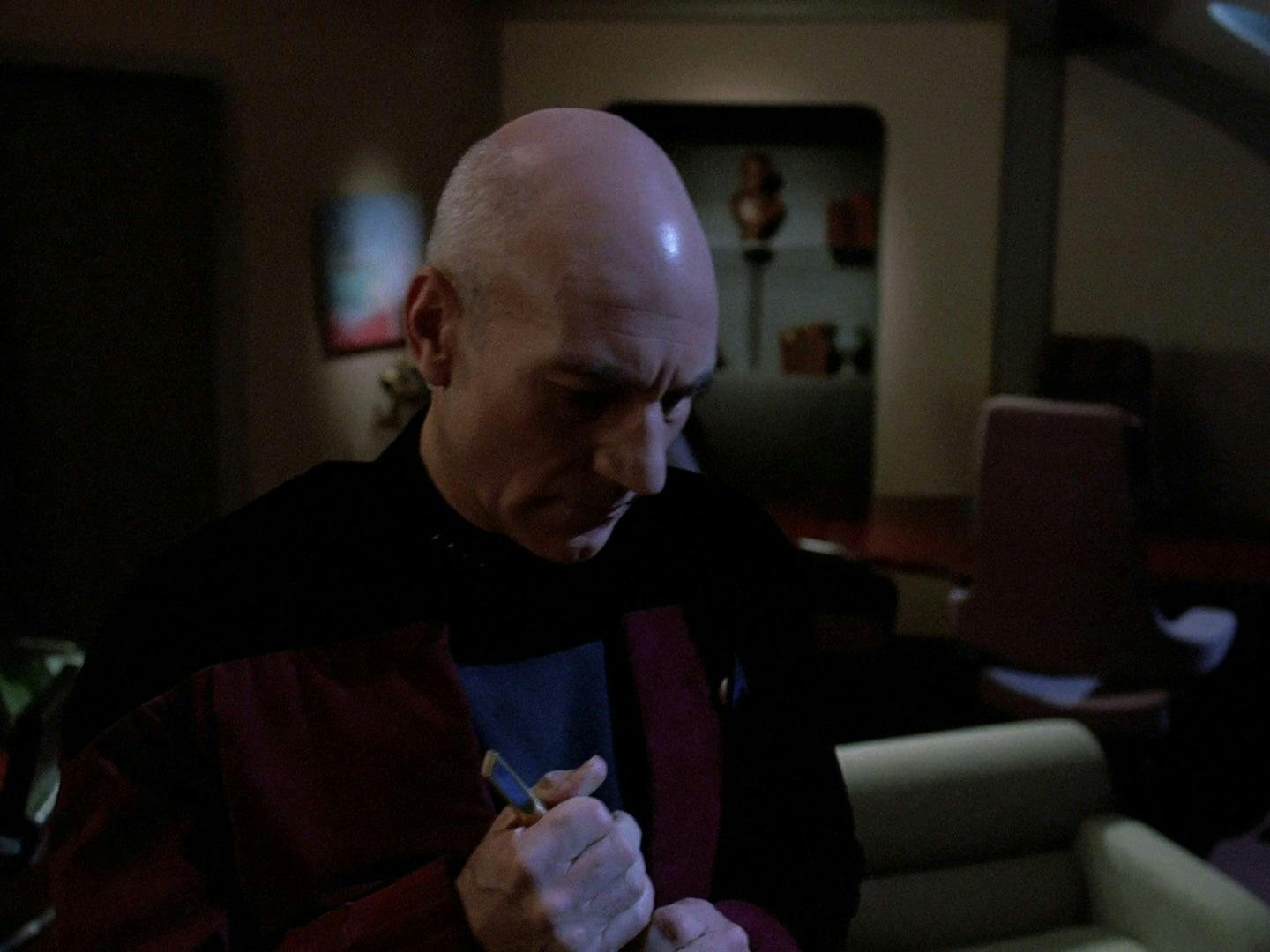

StarTrek.com

The Next Generation is a deliciously peculiar show, and I found myself seduced by its expansive vision of humanity – a humanity that included countless alien races, adorned with putty on their foreheads and sometimes-impenetrable cultural mores, but which never flagged in its genteel optimism that all differences could be overcome, with enough Earl Grey and moral deliberation. On The Next Generation, a psychologist can become a Commander; a blind man can be Chief Engineer; an android can play the violin; and beings can come to understand one another across language barriers through the enduring power of myths and legends – Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at Uruk. Picard’s Enterprise is a floating repository of classical-music concerts, arboretum strolls, and endless interrogations into the finer points of human nature. My favorite TNG episodes were ones like “Remember Me,” in which Dr. Crusher must contend with an ever-shrinking and mutating version of reality – a tight, cleverly constructed horror film in space, whose obstacles are overcome with technology, strength of character and ingenuity. There is an undercurrent of yearning in the show: fan-favorite “The Inner Light,” about the memory of a long-extinct culture living on in Picard’s mind alone, is haunting and tender at once, the story of a lost thing found.

But as May faded into June, and the streets of the United States began to convulse with an uprising for justice – one I joined in small ways, delivering water to a protest, bringing a delivery of cheesecakes to an occupation, donating books to a People’s Library at an occupation of New York’s City Hall – I began to think about The Next Generation’s innate optimism differently. What struck me as I continued to watch the show, dreading its inevitable conclusion even as I continued to gobble up episodes, was the radicalism of the show’s premise, once you considered the things that must have occurred long before Riker grew a beard or Picard assumed the helm of the galaxy-class starship.

The Next Generation’s Enterprise is on an enduring mission of exploration, noninterference, and scientific discovery; it’s staffed by crisp-uniformed, bright-eyed Starfleet Academy graduates, and its staff, as is so cleverly explored in the episode “Lower Decks,” are just as worried about promotion, prestige and being well-liked as any 21st century worker. But in the 24th century, the stakes of these promotions are far lower than our own. In the 24th century, no one has to worry about losing access to their health insurance, or not being able to afford to pay for bread, or dying under the knee of a police officer for the sake of 20 dollars. So much of our contemporary politics are driven by a sense of scarcity – a brutal competition for scant resources that drives some into the arms of racist demagogues, others to strive for equally apportioned justice, and still others treading water too hard to focus on anything but the fight to keep from drowning.

StarTrek.com

As tens of millions of Americans face unemployment, eviction, and starvation, what began to strike me as the most radical element of The Next Generation were the things that had happened before it began: scarcity and poverty had been eliminated, and with it the drive to greed, and the desperation of the have-nots, and clenched fist of state violence shattering the will to upend a status quo that offers nothing to most, and the most to those who need nothing. If you have a replicator, you do not need to engage in exploitative work for bread; and everyone has a replicator in the 24th century. Even in Bobruisk, where Worf grew up, there were no food lines; the biggest concern the Rozhenkos faced was raising a spirited Klingon son, and there was always enough blood pie to go around. We learn that before arriving at the world of abundance created by the Federation, the Earth became a hellish place: nuclear winters, destruction and tragedy beyond measure. That is not hard to imagine, from our current vantage point; it seems imminent, it seems to have begun already. But The Next Generation picks up after the horror has ended; there is a story to be told after destruction ends, about what can be rebuilt from ruin, and the freedom that generosity allows.

TNG is a story of human nature, but part of its innate gentleness is the fact that a post-scarcity economy of infinite resources infinitely shared has taken bread and blood from the equation. What remains are dilemmas and questions that still feel eternal: what does it mean to be human, as Data asks again and again? How can one forget the grief of losing a child, as Lwaxana Troi once did? Why is love – between Riker and Troi, Picard and Crusher – so difficult to keep once you have it?

StarTrek.com

The Next Generation’s quiet radicalism lies there, in the idea that there are so many facets of the human (and nonhuman) experience that lie beyond the all-consuming despair of unmet need. This is what keeps the show running through my mind, like the gentle rise and fall of the song of a Kataanian flute. It’s a generosity modeled by the Star Trek fans who shared their love and joy with me as if there were no scarcity, only abundance; who shared their songs and books and stories with me with eagerness and love. It’s an ethos that dares to imagine what we can explore, what parts of the universe and of ourselves we can uncover, if only we are free of the tyranny of false scarcity; about the new worlds that await us, when we live and prosper.

Talia Lavin (she/her) is a writer and reasearcher based in Brooklyn. Her debut book, Culture Warlords, about white supremacy online, is out October 13 from Hachette Books. Follow her on Twitter @chick_in_kiev.