Published Oct 9, 2019

Seeking Repentance in Star Trek

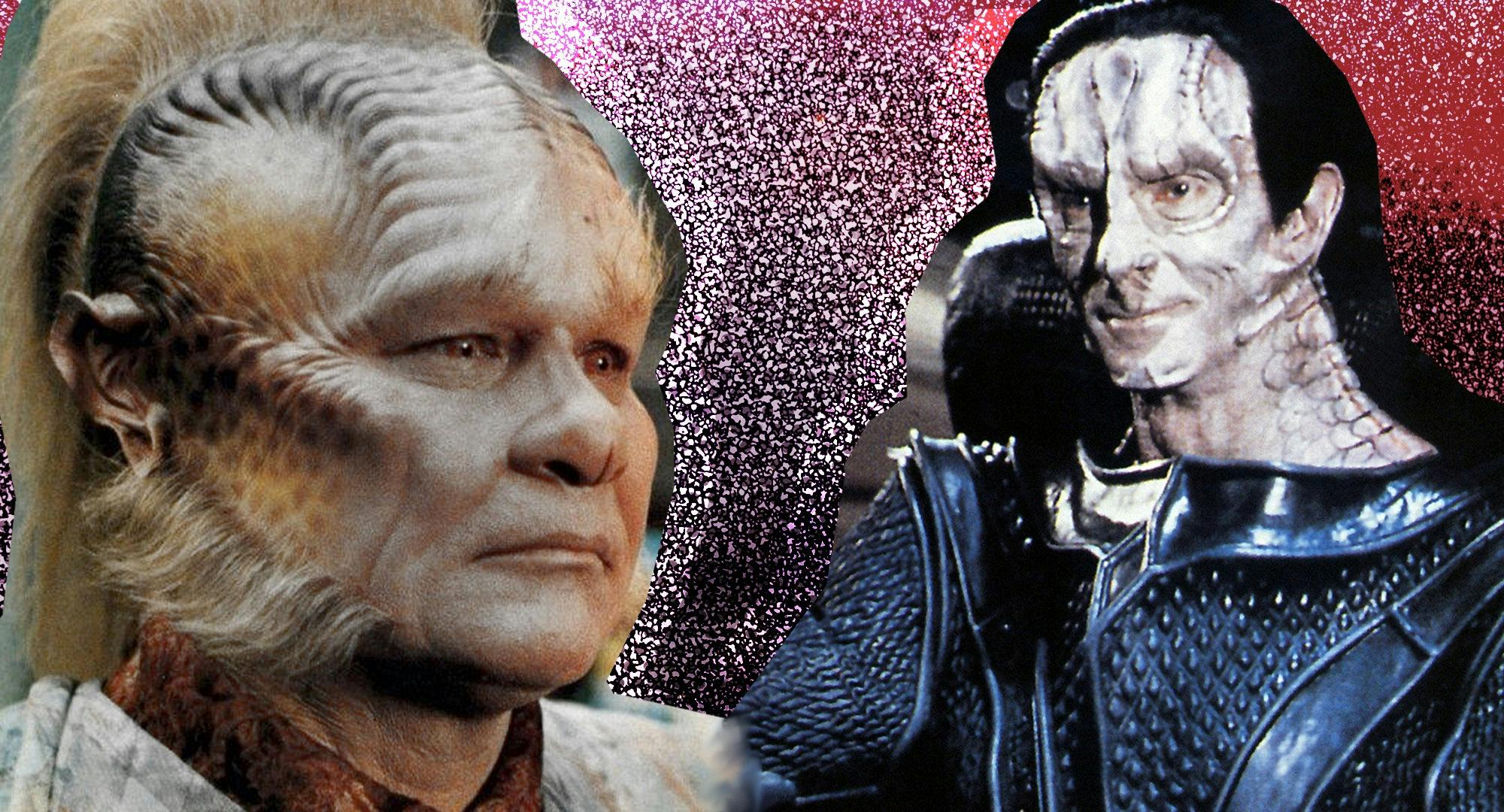

On Yom Kippur, Gul Dukat and Neelix make an important distinction between forgiveness and atonement.

StarTrek.com

Last week, Jews celebrated Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, while also preparing for the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, which we celebrate from sunset October 8 to nightfall October 9. It may be that a fellow Trekker who happens to be Jewish will apologize to you this week, since a central tenet of the Jewish faith is that observing this Holy Day requires each person to seek atonement from G-d for transgressions both against G-d, (which is or is not supernatural, depending on which Jew you ask) and transgressions against fellow humans. Notably, despite the proliferation of apologies, Yom Kippur is not the day of forgiveness because forgiveness and atonement are not the same. Where forgiveness is entirely at the discretion of the victim, atonement to G-d for transgressions against humans requires repentance — an activity that someone undertakes to try to repair the damage they have done in wronging others.

So much of Star Trek — and all good science fiction — can be used to draw parallels to or illuminate facets of the real world, and the show doesn’t disappoint even with something as specific as Yom Kippur. Two episodes in particular, one which focuses on an anti-hero’s quest for repentance and another which focuses on an anti-hero’s quest for forgiveness, can help us understand the right way to seek atonement and the wrong way to seek atonement. Unsurprisingly, DS9 stands out as the series that grapples with these questions the most, and it is not unusual for fans to connect the journey of the deeply religious Bajorans from slavery to freedom to the story of Biblical Jews in the second book of the Torah, Exodus. But DS9 is not the only series that grapples with these questions, and it is to Voyager that we turn first.

StarTrek.com

In the Star Trek: Voyager episode “Jetrel,” Neelix is confronted with the worst war criminal known to his home Talaxian society, a scientist named Dr. Ma'Bor Jetrel. It was Jetrel who designed the “metreon cascade,” a weapon of mass destruction that killed 300,000 Talaxians on the Talaxaian moon of Rinax at the end of a ten year war between the Talaxians and Haakonians. Fifteen years later, Jetrel tracks down Voyager to find Neelix, claiming that the scientist has come to test Neelix for a fatal blood disease called “metremia” that Talaxian rescue workers to Rinax, including Neelix, may suffer from as a result of their exposure to metreon isotopes. Jetrel has spent the last decade and a half since the metreon cascade trying to find a way to repent for his war crime. Though he first claims to Captain Janeway and Neelix that he is seeking to develop a cure for metremia, we later learn that Jetrel has also theorized a way to use the metreon isotopes in the cloud surrounding Rinax to bring victims of the cascade back to life using Voyager's transporter technology.

Jetrel's efforts to bring back metreon cascade victims ultimately fails—even at 120% of recommended limits, Voyager's transporters do not have enough power to pull together all of the subatomic particles of the victims—and Jetrel dies of advanced metremia, ending his research. Despite his failure to bring back those he has killed, it is clear at the end of the episode that Jetrel has done what he believed he could in seeking repentance for his crime: not only does he recognize that what he did made him “a monster” in the view of both his family and himself, but he then spent the remainder of his life trying to repair the damage he had done, even when his persistent efforts resulted in his exile from his own society.

StarTrek.com

Notably, after initially protesting to Neelix that he was just a scientist and that the decision to fire their weapon at Rinax was a decision made by military leadership, Jetrel eventually comes around to understanding that his role in conceptualizing and helping build the weapon of mass destruction is unforgivable. Jetrel admits to Neelix, "There is no way I could ever apologize to you, Mr. Neelix. That's why I have not tried.” The first step to repentance is an admission of guilt.

Jetrel's story of a grievous wrong done against others, followed by a lifetime spent trying to fix what he had broken, stands in sharp contrast to one of the all-time great villains of the Star Trek universe, Gul Dukat. The Cardassian leader spends much of DS9 avoid avoiding confrontation with the consequences of the atrocities he committed during the Occupation of Bajor. One episode serves as a case study in Dukat's unwillingness to seek repentance for his actions, instead seeking only unearned forgiveness.

“Return to Grace,” takes place in 2372, during the Klingon wars with both Cardassia and the Federation. Major Kira Nerys is transported by Gul Dukat, now captain of the Cardassian freighter Groumall, to a conference between Cardassia and Bajor where Bajorans intend to share important intelligence about the Klingons. They arrive, however, to find the outpost destroyed by a Klingon Bird-of-Prey. Kira and Dukat team up to modify the Groumall so that it is capable of chasing down and destroying those responsible.

StarTrek.com

The central plot of “Return to Grace,” however, is not what is most revealing about how Dukat views repentance and forgiveness. Unlike Jetrel, who we see in only one episode, Dukat is a recurring character who repeatedly fails to admit that he has done wrong, even at his death refusing to atone for his war crimes. As illustrated in “Return to Grace,” Dukat cares only about gaining Kira's unearned forgiveness and does not even care to truly work toward earning it. Kira even sums this up for the audience when she tells his daughter, “Ziyal, what your father wants from me is forgiveness. That's one thing I can never give him.” In fact, Dukat never really asks forgiveness for his gravest misdeeds, only at one point responding to Kira after she attempts to set boundaries with him, “I’m sorry, Major. I didn’t mean any harm. I was only making conversation.” There is no repentance in this apology.

On Voyager, Jetrel understood that what he did was something so horrible that an apology was meaningless, and that forgiveness could be given only by the victim. Dukat, on the other hand, never truly accepts or understands his role in the Occupation, which killed fifteen million Bajorans. This contrasts against the outcome of the episode’s B-plot which is Kira confronting her common past with Dukat as a soldier who is responsible for killing people. In the end, Kira repents by trying to end the cycle of violence and protecting Ziyal from having to live the life that a resistance fighter lives. “The best way to survive a knife fight is to never get in one,” Kira tells Ziyal. This is Kira’s atonement.

StarTrek.com

Yet instead of seeking to repent for his past crimes, the title of the episode reveals what Dukat was truly after: grace, the unmerited and free salvation of a sinner. Grace is required here because Dukat refuses to take responsibility for his sins. The “grace” he seeks is in fact a return to power; rather than feel remorse or guilt for his role in oppressing, killing, raping and torturing Bajorans, Dukat wishes to return to a position where he again has that sort of power over others. Near the end of the episode, Dukat tells Kira, “There was a time when the mere mention of my race inspired fear. And now… we're a beaten people. Afraid to fight back because we're afraid to lose what little is left.... Don't you see, Major? They're paralyzed. They're beaten and defeated. I am the only Cardassian left, and if no one else will stand against the Klingons, I will.” In these words, there is no remorse, no atonement. There is no understanding of why the Cardassians have had their power circumscribed – a consequence of their violation of humanoid rights.

StarTrek.com

These episodes hammer home the lesson that forgiveness cannot begin when there is no repentance in sight. In the final scene of “Jetrel,” Neelix delivers a final message to the dying Jetrel: that he forgives him. Jetrel never sought that forgiveness and in fact thought it was something he could never ask for. Recognizing that what he had done was destructive, Jetrel instead spent the end of his life seeking to undo at least some of the horrors he had unleashed. He is an example of looking at and owning the worst parts of oneself, and then trying to do something about it. Dukat, on the other hand, is an example of what happens when someone can't even admit to having done anything wrong. The lesson of Yom Kippur is that what matters is the repentance.

But the secret — which Dukat failed to learn — is that forgiveness is just a bonus.

Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein (she/her) is an Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy and Core Faculty in Women’s Studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her research focuses on cosmology and particle physics. Find her on twitter @IBJIYONGI.