Published Aug 25, 2020

Exploring the Beliefs Behind Star Trek’s Heroes

Forget what you know —what do you believe?

StarTrek.com

“Man is what he believes.” — Anton Chekhov

Forget what you know — what do you believe?

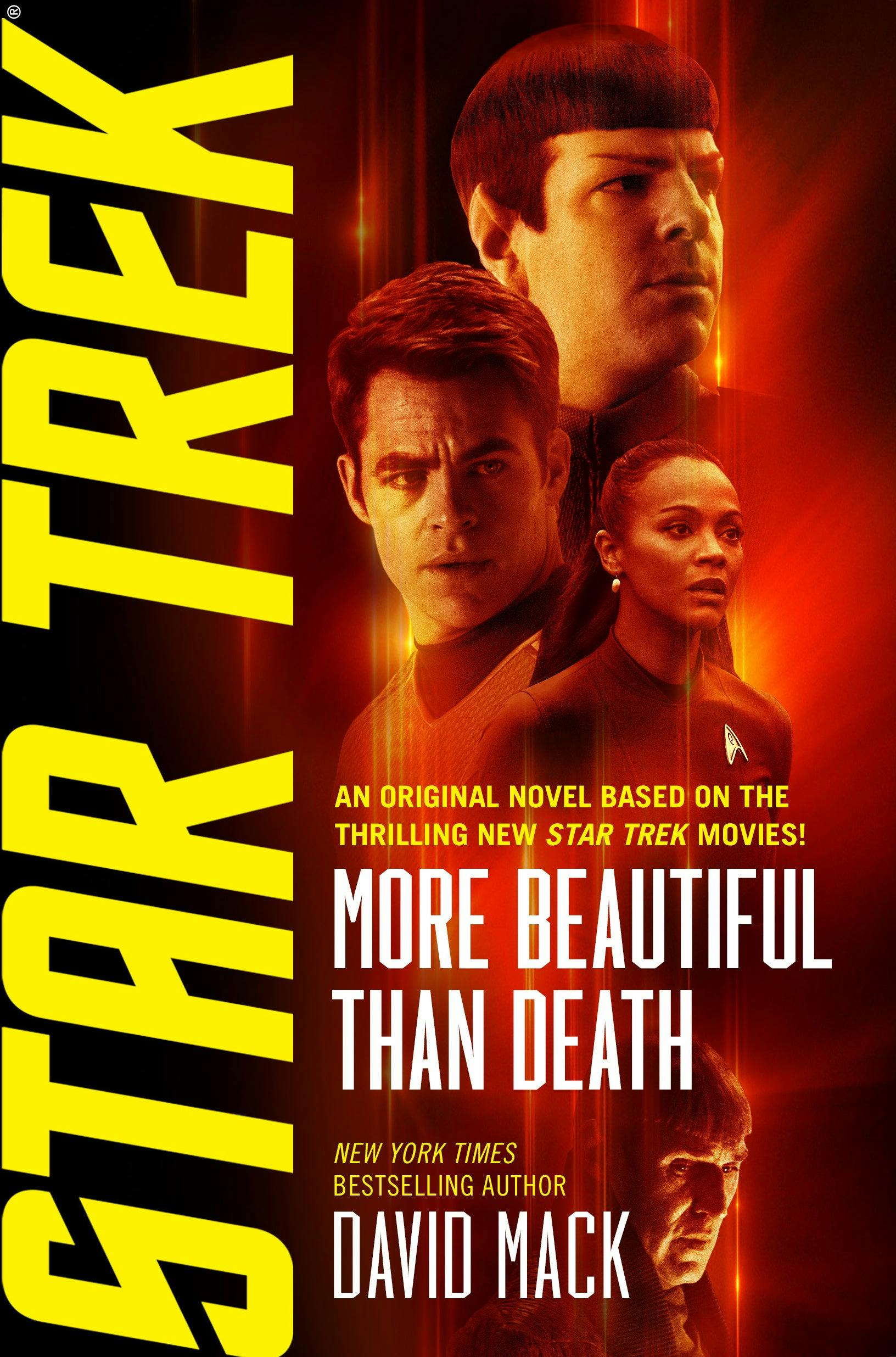

Since the earliest days of science fiction, one of the cornerstones of the genre has been to question what we think we know. This is rooted in the scientific aspect of the genre’s roots. Science fiction has on occasion also dared to tackle less well-defined questions of belief. It has often done so from a standpoint of skepticism, especially in the televised adventures of Star Trek. However, many episodes of Star Trek have explored questions of belief in good faith (pardon the pun), and that was what I set out to do when I wrote my Star Trek novel More Beautiful Than Death (out now from Gallery Books).

Over the course of seven seasons, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine did a wonderful job of exploring the intricacies of the Bajoran religion. Similarly, Star Trek: The Next Generation and DS9 both excelled in their exploration of the Klingons’ mythology and spiritual beliefs, and Star Trek’s investigation of the idea of the soul includes not only the revelation of the Vulcan katra (in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock) but also the many thorny questions raised in such episodes of The Original Series as “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” and “Requiem for Methuselah.”

Not all matters of belief need be spiritual, of course. A person could put their faith in a secular ideal, such as democracy, or in a philosophical principle, such as compassionate humanism. There are many intangible virtues in which one can choose to place one’s hope for the future.

Those ruminations, however, led me to wonder—what does Captain James T. Kirk believe?

StarTrek.com

Kirk spurns Apollo’s demand for worship in the TOS episode “Who Mourns for Adonais?” by telling the self-exiled Greek deity, “Mankind has no need for gods. We find the one quite adequate.” This seems at first to suggest that, in his mid-thirties, Kirk subscribed to some variety of one of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, or Islam). At the very least, it implies that Kirk is aware that a majority of the human population of the mid-23rd century is invested in those religions.

Likewise, in the feature film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, the intrepid captain bristles when, at the center of the galaxy, he confronts a being who claims to be God. He sees through the being’s charade almost instantly: “What does God need with a starship?”

Some friends with whom I saw Star Trek V in the theater interpreted that scene to suggest that Kirk didn’t believe in God. I think, however, they might have been mistaken. I think it’s possible James Kirk did believe in a truly benevolent, loving higher power—and that he believed in it so sincerely that he could not possibly accept an impostor whose motivations were rooted in malice and self-interest.

There is ample evidence from TNG that Captain Jean-Luc Picard is an atheist to his core, as well as a staunch humanist with a firm grounding in philosophies of nonviolence and compassion. But Captain Picard is the product of a society nearly a century past the upbringing of James T. Kirk. I think it’s not out of character to imagine that Captain Kirk might have been open to a spiritual understanding of his own existence, and of the universe.

That notion — that Kirk might be willing to consider such concepts as having had “past lives” — was part of what inspired me to write my Star Trek novel More Beautiful Than Death. Because my book is set in the universe of the new cinematic version of Star Trek, and features a younger, brasher incarnation of James Kirk, this seemed like a prime opportunity to expand the young captain’s mind by challenging his societally instilled belief in a rational, deterministic universe.

StarTrek.com

At the same time, I devised conflicts of a more personal and emotional nature for Spock, his father Ambassador Sarek, and Nyota Uhura. I wanted to force each of them to confront the beliefs they held to see if they could withstand rhetorical assault. I made Spock justify to his father the role he has chosen for himself in the new, post-calamity diaspora society of Vulcan, while at the same time I made Uhura conquer her own doubts about her love for Spock.

I think that by the end of the story, Spock, Sarek, and Uhura have all learned something about themselves and/or their relationships to one another. But most of all, writing this novel led me to discover what I believe is at the heart of James T. Kirk, the truth that drives him and makes him who he is. I hope my readers will feel I did justice to the new cinematic versions of these iconic characters, and that I depicted their profound inner and outer conflicts with honesty and fairness.

Until next time, as Journey once sang, “Don’t stop believin’.”

More Beautiful Than Death is available for sale here.

Ethan Peck Reads Too Many Tribbles

David Mack (he/him) is the award-winning and New York Times bestselling author of 36 novels and numerous short works of science-fiction, fantasy, and adventure. His writing credits span television, film, and comic books. He currently works as a consultant on two Star Trek animated television shows, Lower Decks and the upcoming series Prodigy.