Published Nov 28, 2015

Creating Official Trek Magazines (1983-2000)

Creating Official Trek Magazines (1983-2000)

My life, for 17 years (1983-2000), was haunted by licensed magazines. During that fabled era, I served as Editor of about 110 of them (84 of those Star Trek-related). I also assisted colleagues who edited another dozen+ of the nearly 150 total licensed magazines issued by Starlog Press (a.k.a. O'Quinn Studios, Starlog Communications, Jacobs Publications, Starlog Group). We'll get to the Trek stuff shortly. First, let's define terms.

Just what is a licensed magazine? It's a product little different from a T-shirt, toy or action figure (except you can read it). Like those types of merchandise, a publisher pays a studio (or other copyright/trademark holder) for the rights to exclusively issue tie-in publications (often one-shots for movies, ongoing periodicals for TV series). Publishers can't legally put out either a one-shot or an issue of a regular periodical focusing solely on a single Intellectual Property (owned by another entity) without risking courtroom retribution. In other words, if you don't bother to obtain any rights to that IP and just publish a Transformers one-shot or The Big Bang Theory Monthly, look for "Cease & Desist" letters in your in-box and the inevitable knock-knock on your door from lawyers smiling sharply.

However, there is the so-called "Rule of 60 Percent" (that's the percentage I was told)---i.e., one-shots and ongoing magazines are legally in the clear if they don't go all the way and instead devote no more than 60% (or whatever %) of their content to that single subject IP. You still see publications exploiting this "fair use" loophole today (most recently with Hunger Games and Harry Potter material). In fact, that's how Starlog Magazine itself started back in 1976---as a one-shot initially entitled Star Trek until legal concerns surfaced, other science fiction topics were added to the lineup and the name changed. Brisk sales subsequently sped Starlog from one-shot to quarterly and then monthly publication. And, a few years later, the company was actually licensing Star Trek from Paramount Pictures for Official Magazines.

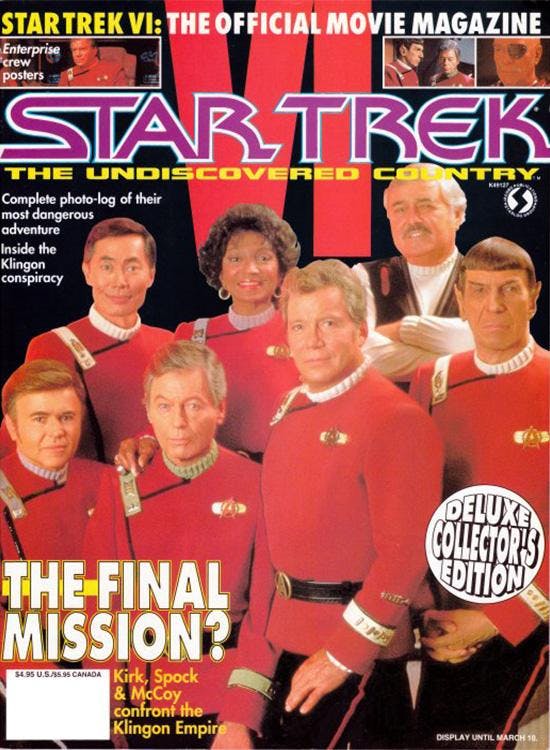

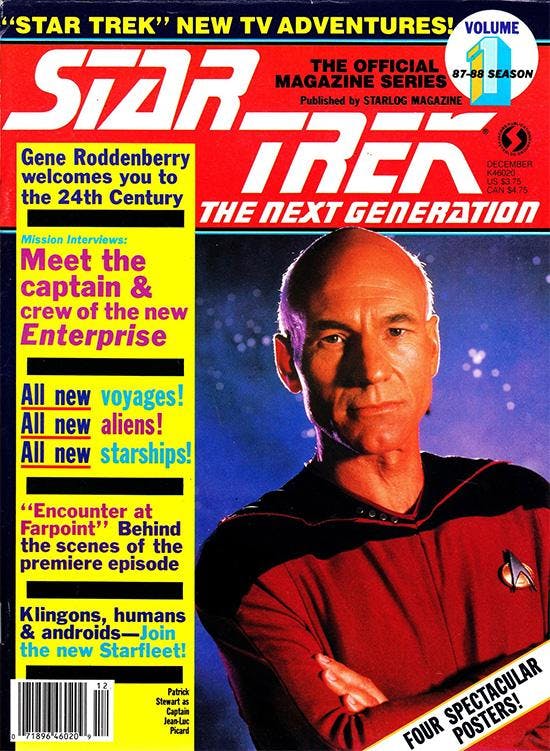

To be far too specific about my licensed Star Trek output (1984-98), I served as Editor of nine publications showcasing five films (all Movie Magazines plus others as noted): Trek III (also a Poster Magazine), Trek IV (also a Poster Mag & a Movie Special), Trek V, Trek VI, Generations (also a 3-D Cover Special Edition variant). I edited the Star Trek 25th Anniversary Special (1991). And I was Editor of three ongoing Trek TV titles: Next Generation (#1-#30, all seven seasons), Deep Space Nine (#1-#25, first six seasons) and Voyager (#1-#19, first four seasons). Additionally, I assisted Editor David Hutchison on his two licensed Next Generation projects (The Technical Journal, The Makeup FX Journal).

In 1982, I edited two non-Trek Paramount Movie Magazines: Explorers (1985) and The Phantom (1996, actually licensed from King Features, film made and distributed by Paramount). Grand totals: 91 Paramount projects published by Starlog Press, 86 edited by me; 87 of that Starlog Press output are Treks, 84 of them edited by me. I'm exhausted just listing all this stuff. How 'bout you?

With licensed magazines, the details can really give you the Devil. Unlike a regular publication (i.e., Starlog, Fangoria or Comics Scene), being licensed also allows the licensor to see and approve every word, photo and layout (including the cover) of the entire magazine before it gets printed (the enigmatic "approval process") and change anything they wish. On my first such project (High Road to China, December 1982-February 1983), I interviewed its director, Brian G. Hutton (who also helmed two of my favorite WWII adventures, Where Eagles Dare and Kelly's Heroes). He told me that people had died in an air accident during the movie's making. Naively, I included that sad fact in my magazine licensed from the Golden Harvest Company---AND THEY LET ME! Had we (i.e., Golden Harvest and me) all been on the ball during the approval process, such tragic, controversial, possibily litigious incidents would never have seen print in a licensed product.

Two years later, there was Explorers, my Paramount-licensed publication showcasing that Joe Dante-directed fantasy adventure (which features a Starlog Magazine on-screen cameo and Voyager's Bob Picardo, a Dante cast regular, in wacky alien makeup). Randy Lofficier (an American writer who collaborates with her French husband, Jean-Marc) interviewed Dante, producer Mike Finnell and the film's then-kid stars (Ethan Hawke, River Phoenix, Jason Presson, Amanda Peterson). Quizzed separately, all six detailed the filming difficulties which arose when Hawke broke his foot. Those innocent quotes were included in the Lofficiers' six written profiles of them. We finished the project, sent the magazine layouts in for approval and waited. And waited. Finally, Finnell, the producer himself, rang to dictate changes.

In fact, Finnell called me less than 24 hours before we had to go to the printer or risk missing our new on-sale date (accelerated when the film shifted its premiere)...at home...on my birthday...just as friends arrived to take me out to dinner (and they impatiently waited while I attended to business on the phone). Finnell declared, "There's an over-emphasis on Ethan's broken foot." And he demanded we delete every quote noting Hawke's injury---including Finnell's own mentions of it. Wow! Note the devilish difference in licensed mags: Death is A-OK on the High Road to China, but a broken foot is forbidden to Explorers. I was so annoyed by this (in my view) silly alteration that I put Explorers on the cover of Starlog #98! Yes, that'll teach them!

Unlike Finnell (or producer Gale Anne Hurd on my Aliens publications in 1986), Paramount's Trek producers (Harve Bennett, Ralph Winter, Gene Roddenberry, Rick Berman)---with millions of dollars in production foremost on their minds---didn't personally attend to Official Trek Magazine approvals. The studio had people for that. And, over the years, I worked with several different licensing liaisons on all our Trek projects.

One of them---who I never dealt with directly regarding these matters, others forwarded his comments to me---requested numerous changes (some helpful in creating better issues, others not so much). Bizarrely, I already knew him, and we subsequently lunched together with two other folks at an event. He complained for several minutes about "how they do things at Starlog," apparently not realizing that the "they" to which he referred was actually me! Or, devilishly, maybe he did know---and he was just messin' with me.

Another licensing guy had a military background---and suddenly all our Starfleet Naval/military terms in articles and episode synopses were made "shipshape and Bristol fashion." He also pointed out that we shouldn't have the Enterprise "radio" other starships since that medium (and any outdated language references to it) would be "long gone" in the 23rd Century. So, we used "contact" instead. Beyond regular Trek standards, all these Paramount Licensing people had different concerns like that, stylistic "hobby horses" we addressed despite the inconsistencies they might spawn overall (don't get me started on Bridge vs. bridge and other standing sets' capitalization concerns). Fortunately, everyone was united in wanting the best possible publications we could create at the time.

Two final Trek TV tales, one short, one not. An article we submitted for OKs was disallowed! Turns out the Trek interviewee---alerted to our intended publication by an innocent photo request---had actually granted that chat to the reporter involved for a different press outlet. When it got detoured into my devilish clutches instead, said interviewee was miffed and asked that the piece (which had nothing remotely controversial or negative about it, no deaths or broken actor parts) not be used. I was happy to comply; by the time I heard his objections, I didn't much want to run it anyway. Yes, that'll teach them!

On another occasion, I bought an interview done nine months previously by a writer new to me (I was ever-hungry for material since there was always space to fill in my Trek "books"). The piece was edited, designed and even approved by Paramount. Off it went with the rest of the issue to the printer! Another one done, on to the next! However, a day or two later, my liaison called with a problem. Merely as a courtesy, photocopies of that layout had been innocently sent to the person profiled who---uh-oh!---was disappointed because "the quotes were old." Now, this person had absolutely no contractual right to approve that article (or even see it pre-publication), but, nonetheless, we were now in a devilish situation.

To further complicate matters, it was (I'm not kidding!) the Cover Story. And if that Trek magazine, at the Midwest printing company (where it all already was), wasn't on press within 72 hours, that issue wouldn't make its on-sale date. And that would be---Death!

Let me pause here in anecdotal remembrance to explain that "Missing an On-Sale Date" is as forbidden in magazine publishing as broken body parts on Explorers. It creates a chaotic cascade of catastrophes! In English, that means, when issues printed late show up after the promised date (maybe a week or two later), it messes up computerized accounting (and cash flow). To simplify matters, the magazine's sub-distributors and/or individual sales outlets sometimes just "premature" that issue (simply refuse---or neglect---to go to the trouble of placing late copies on store shelves, thus giving them absolutely no chance at all to sell; instead, these undisplayed numbers are just "prematurely returned" for "not sold" financial credit).

Any delay also cuts into sales time (giving a bi-monthly like Deep Space Nine, Voyager or Next Generationjust six or seven weeks of rack display, instead of the full eight, because, presumably, the next issue arrives on time). Falling sales due to prematuring and/or less shelf time cue decreased revenue (for Starlog) and royalties (for Paramount). Enough of all that and pretty soon, there's no magazine anymore.

Was it even possible to pull a story back from the printer when the entire issue was already there? Never did that before! And I did point out to my liaison that the whole book had been OKed, so legally we could maybe, probably, possibly go ahead and just print it. But proceeding on that devilishly fine point might get my liaison in trouble (reprimanded or fired) and institute a more difficult future approval process for us all. We had to fix this problem.

To cut to the chase, here's what happened: The printer agreed to hold off "plating" that five-page Cover Story (while prepping the rest of the book for press). Paramount Licensing purchased for us the rights to another, newer interview that the protesting person "liked." Its content thus "pre-approved," this shorter story was either e-mailed or FAXed to me that very day. We copy-edited, typeset and proofread it. The old text was deleted from our duplicate layouts by my designer; he stripped the new text and byline into the old layout, all photos and previous captions remaining as is. However, there was less new text so it didn't fill all the space. Pragmatically, I coped with this unanticipated shortfall by simply killing one-page of the original layout and replacing that with an already OKed house ad. We FedExed the revised pages to the printer, printed on schedule and made that crucial on-sale date. And the person who prompted all these nightmarish, rapid-fire antics from everyone else ended up with a Cover Story that's actually one page shorter than once designed. Yes, that'll teach them!

Copyright 2015 David McDonnell