Published Jun 25, 2015

Trek's Oldest Living Actor Speaks

Trek's Oldest Living Actor Speaks

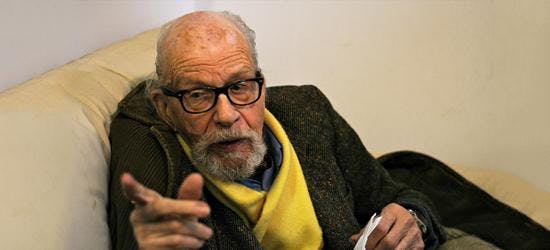

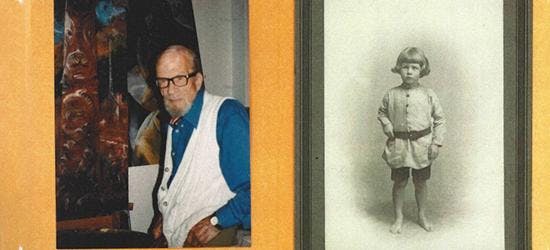

Olaf Pooley, at 101 years old, is the oldest living actor to have appeared on Star Trek. The Brit, who has lived in Los Angeles for many years now, also happens to be the oldest living actor to have appeared in Doctor Who. His acting credits span decades, he once directed a fledgling young thespian named Anthony Hopkins and he was married to Star Trek’s first female director, Gabrielle Beaumont. It was Beaumont who tapped Pooley, her husband at the time, to guest star as the Cleric in her Voyager episode, “Blink of an Eye.” Pooley’s role was short and sweet, but this interview is extensive – and far more about his life than his Star Trek experience. But it’s fascinating stuff, and so we’ve decided to include every word of it. Among the topics of conversation is a GoFundMe campaign set up by a family friend to help raise funds to buy Pooley dentures, as his teeth, but not his mind, have lost their battle with the ravages of time. So sit back, grab some tea and enjoy our detailed conversation with Mr. Pooley.

At the end of the war I had made a lot of friends in the theater and I continued. I had a big following in radio, I did a lot of work for the BBC and had quite a following. Of course, it’s funny now, because later in life, I returned to my first love, which is painting and I have accomplished quite a lot in that field and still keep a studio down at The Santa Monica Fine Arts Studio, down at Santa Monica Airport. I wish I could get down there more often, but at 101 you don’t have the energy.Who were your acting contemporaries back in England?POOLEY: It’s a long while back, but I knew so many. My closest friend was a lovely actor named Michael Gough, who became known to American audiences playing the butler in the first Batman movies. He was a wonderful actor and was in so many different TV shows and movies. I knew Noel Coward and worked with him in one of his plays, Peace in our Time. I played the traitor who gets shot at the end of the play. I knew Sir Michael Redgrave, Alec Guiness and his wife Merula before, of course, he became “Sir” Alec. And there were countless people who came into my life including Sophia Loren and her husband Carlo Ponti. I was asked to do some script doctoring for them and went to Italy. I think we began in Rome and ended up in Calabria. Max Schell was a dear friend, too, and I knew Omar Sharif, who was such a gentleman. But there you are... when I look back now, all my contemporaries are no longer living.

The goal of the GoFundMe page for Pooley is to raise $3,000 to pay for dentures to replace the teeth he's lost to age. Visit GoFundMe to contribute.

---

Follow us for more news at StarTrek.com and via our social media sites.