Published Jun 15, 2013

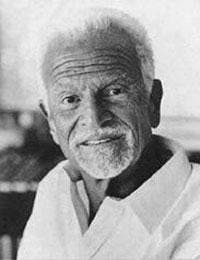

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: TOS Composer Gerald Fried

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: TOS Composer Gerald Fried

Your stated philosophy about music is that its function in any movie or show is to make it a better movie or show. So, the question is, How do you go about crafting music that does that?

FRIED: You have to break it down to the component parts. Where should the music be? What should the music say? Should it go with the scene as it’s shown or should it get into some subtleties that are not visual? You have a car chase. OK, but what if the driver just found out this his mother died, and that’s what’s going through his mind during the chase? So, you make a series of those decisions and that gets you to what music should do. I still get annoyed at movies and shows that turn into music-plugging devices, that have music supervisors who try to stick in as many pop-type tunes as possible. I love movies and television and music too much for it all to be reduced into a song-plugging device. If we had to do it for an end title, at least I tried to use a song that was appropriate and in character.How did you connect with Star Trek?FRIED: Do you want the truth or the story?Both…FRIED: The story is better. I dreamed one night that Gene Roddenberry was thinking about me and that I was the person to do Star Trek. And, sure enough, the next morning Gene called and said… No, OK, that’s the bulls—t. The truth is that my agent called and said, “Gerry, 10:30 at Desilu. There’s a series called Star Trek.” I said, “OK,” and I showed up. See, the truth is not as good as the bulls—t.You scored five episodes of Star Trek. What memories/anecdotes can you share with us about them?

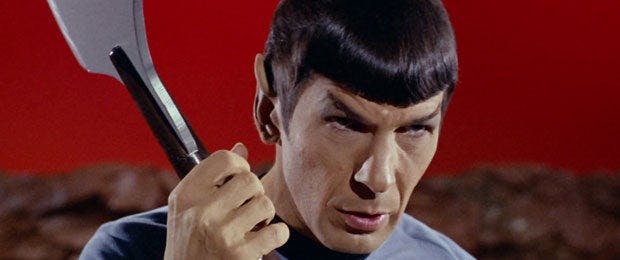

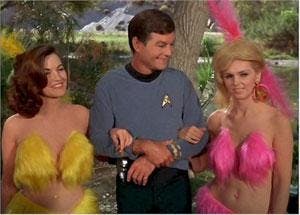

at it was supposed to be science-fiction and outer space and all of that, but that the story was also so pertinent and insightful to us humans on Earth. Theodore Sturgeon wrote that and I love him for his introspection. I was able to do different kinds of music, because of the fantasy, and that was kind of fun. It was a chance to show off some versatility. “Catspaw” was entertaining. Cat, to me, means clarinet and not just because of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. The sound of the clarinet is like the sound of a cat’s footpaw; you can’t hear it, but you feel it. So I wrote for, I think, six clarinets for that episode. Just having fun with all those clarinets dominated my thinking doing that episode. “Friday’s Child” had a Native American kind of a feeling to it. By that time, I was thoroughly enjoying my work on Star Trek and I loved getting calls to come in and do another episode. Nothing specific comes to mind about that one, though. “The Paradise Syndrome,” that I kept as folk and as all-purpose native as possible. And the one that most people seem to talk about is “Amok Time.” Once again, I was impressed with them telling a mortal, earthly story. It was about rivalry and fighting for a girl, and that was just plain old fun, putting music to that. Can we assume that scoring these episodes, you had the episode in fronat it was supposed to be science-fiction and outer space and all of that, but that the story was also so pertinent and insightful to us humans on Earth. Theodore Sturgeon wrote that and I love him for his introspection. I was able to do different kinds of music, because of the fantasy, and that was kind of fun. It was a chance to show off some versatility. “Catspaw” was entertaining. Cat, to me, means clarinet and not just because of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. The sound of the clarinet is like the sound of a cat’s footpaw; you can’t hear it, but you feel it. So I wrote for, I think, six clarinets for that episode. Just having fun with all those clarinets dominated my thinking doing that episode. “Friday’s Child” had a Native American kind of a feeling to it. By that time, I was thoroughly enjoying my work on Star Trek and I loved getting calls to come in and do another episode. Nothing specific comes to mind about that one, though. “The Paradise Syndrome,” that I kept as folk and as all-purpose native as possible. And the one that most people seem to talk about is “Amok Time.” Once again, I was impressed with them telling a mortal, earthly story. It was about rivalry and fighting for a girl, and that was just plain old fun, putting music to that. Can we assume that scoring these episodes, you had the episode in front of you and recorded the score with an orchestra?