Published Jan 21, 2013

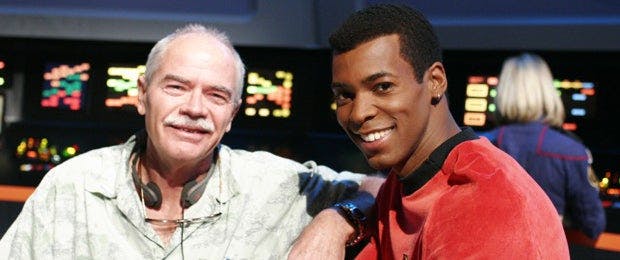

Catching Up With Trek D.P. And Director, Marvin Rush, Part 1

Catching Up With Trek D.P. And Director, Marvin Rush, Part 1

Marvin Rush’s ride through the Star Trek universe cut across parts of three decades, as, from 1989 to 2005, he served as the director of photography for The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager and Enterprise. Rush also directed five episodes of Trek, spanning three series. He helmed “The Host” for TNG, “The Thaw” and “Favorite Son” for Voyager and “In a Mirror Darkly, Part II” and “Terra Prime” for Enterprise. Since the demise of Enterprise in 2005, Rush has worked as a cinematographer on the series E-Ring, Close to Home, Moonlight, Glee and the current Hell on Wheels, as well as the indie features S. Darko, Cherry and Meeting Evil. StarTrek.com caught up with Rush recently for an extensive interview in which he discussed his work as a D.P. and director on Trek and chatted about his latest projects. Below is part one of our conversation, and visit StarTrek.com again tomorrow for part two.

Before we delve into your Trek work, please give people a sense of what it is a director of photography actually does.Rush: The cinematographer is in charge of the photographic look of the show. So, the elements a D.P. has a lot of say so in are the shots themselves, how they’re operated or executed, how the scenes are lit, the mechanical, physical setup of shots and also the coverage of the scenes: how many setups, what will constitute with the coverage. Now, these overlap with the director, but an awful lot of the responsibility is the D.P.’s. It varies a bit with the director. Some have a stronger hand in these areas and some do not. But, certainly in terms of lighting and camerawork, that’s the job of the director of photography.How did you connect with Trek back in the late 1980’s?Rush: I was on the Paramount lot. I’d worked on several sitcoms, and one of them was a one-camera show called Frank’s Place. It’s probably little-known today, but it won a Peabody Award and it was a very, very interesting half-hour comedy-drama set in New Orleans. That was my only one-camera credit. I’d also done the first 13 episodes of The Tracey Ullman Show. That was more of a variety show and not exactly a sitcom. But I’d been known, at that point, mostly for sitcoms. So that’s what I was doing on the Paramount lot. One day, an executive came over to me and said, “Hey, we’re thinking about making a change next season on TNG. Are you interested in doing a one-camera show?” I mean, this is what I’d dreamed about my entire life, my whole career, the chance to move up the ranks and do a one-camera drama. Star Trek was one of those iconic shows. TNG had only been on for two seasons then, but it had already attracted somewhat of a following. I hadn’t really watched much of the show, but I was aware of it. Of course, I was very aware of the original show and had watched those episodes. I wouldn’t call myself a Trekkie, but I was familiar with the work.Anyway, I told them, “Sure. If that’s a possibility, absolutely.” So, after a little while, they kicked it around and then said, “Come in for an interview.” The three people I had to pass muster with were Rick Berman, Peter Lauritson and David Livingston. As luck would have it, all three of them were fans of Frank’s Place. They were very familiar with the episodes and with the photographic look, which was anything but sitcom. We shot that like a little miniature movie, and we took great pains to get it right photographically, as much as the time would allow. So the interview was interesting because they asked me, “Well, are you a Star Trek fan?” I couldn’t really say I was. I said, “I’m pretty familiar with the stuff, but I’m not a Trekkie.” Interestingly enough, that was actually a positive thing. I think they didn’t want somebody who was too enamored of the genre, of the franchise, to the extent that they weren’t necessarily looking at it was fresh set of eyes. So you got hired and took over as director of photography starting with season three of TNG…Rush: Yes, I then did season three, four and five. Those were really, I think, a high-water mark in terms of Trek storytelling. I always feel like those were the best shows I did, with a few exceptions. Voyager had some really high moments and DS9 and Enterprise had a couple of high moments for me as well, but I think the entire three years on Next Gen were pretty fantastic. Also, I was growing as an artist in that timeframe, so for me it was a really special time in my life, very important.Let’s get more specific. You walked in the door with, as you say, mostly a sitcom background. What were the challenges you faced capturing TNG on camera?Rush: Television, just in general, is done at a furious pace. The amount of work you need to get done every single day is daunting. If anything goes wrong… Just using Star Trek as an example. You had a lot of actors in makeup. You had a fancy wardrobe that was finished just before the actor hit the set. If anything went wrong with anything, you lost time while those things were made right. Well, they don’t give you more time in a day to get the scenes shot. You’ve got to find a way to get them done on schedule. So there’s a lot of time pressure, and I think that’s the hardest part: doing your very best and also doing it at a remarkably fast pace.On television, directors come and go, yet every director wants to make his or her mark on the episode, on the series. How often did you find yourself having to say, “Sorry, but we don’t do that on Star Trek” or “We can’t do that” or “We just don’t have time”? Or was that not your place?Rush: Philosophically, I’m predisposed to saying “Yes.” I think I’ve always thought, “Well, how would I feel if I were directing an episode and somebody comes to me and says, ‘We don’t do things that way?’” So, I always tried to make it a point to never say things like that to directors. However, what I would do is say, “How much time have you allotted for this sequence? This two-page scene may take more time that you’re thinking. If it takes four and a half hours, are you OK with that or will that destroy the rest of your day?” I’d explain, “We can’t get any more time and all that will happen is the office will come down and breathe fire down our necks, and it’s not going to be fun.” So that’d be the way I’d handle that. It’d never be about not wanting to do the director’s vision. If there was a situation where a director wanted something I didn’t’ think would work well, that I thought wouldn’t tell the story, I’d feel like I at least had a responsibility to debate it until we had a clear understanding of why it was a good idea and how we could do it. But, just in general, my focus was always on saying “Yes” to directors and not really giving them a lot of grief about how to tell a story, because that’s their business.

DS9 rolled around and you came on board as director of photography. Everyone talks about it being a different Trek, the darker Trek. In what ways was or wasn’t it different from your end of the world?Rush: There’s an interesting story about that. I always thought that the best way to contrast the two shows was to use two iconic comic books. So, for instance, if you said that TNG was akin to Superman, well then DS9 is akin to Batman. It was a darker, brooding, more foreboding place. Keep in mind that the station was a Cardassian structure. So it was a different civilization, a much darker, more sinister civilization. So the idea was to make it look darker and more sinister. The interesting story is that, in the course of getting ready to shoot the DS9 pilot, I shot some tests. After the producers looked at the tests, they said, “Marvin, this is too dark. This is way too dark.” I said, “I can brighten it up a little bit.” So I went and the next day I shot some more tests. I just reduced the contrast a bit, added a little more fill and maybe made some of the areas a little brighter. They came back and said, “Still too dark.” I said, “OK. Let me show you what the set will look like if I light it bright.” I lit the set the next day with a very broad lighting, more like the bridge of the Enterprise, with its overhead domed ceiling, which was very, very bright. I’d parenthetically say, “That was true on the Enterprise, until things went crazy, and then they got progressively darker and darker and more contrast-y, until the resolution at the end, when the lights came back on.” That was basically the way to show the drama of change on TNG.So I showed them, for DS9. I lit the set up with a lot of light, from every direction. We looked at the test and there was silence in room. All the producers, directors… everybody was there, and there was total silence. I said, “Guys, the set looks like it was made out of injection mold and plastic. This is terrible. I could probably move it back a little bit, but it’s not going to have a distinctive style. It’s not going to look like anything different than TNG, except that the set looks different, but it won’t have any of that ominous, foreboding quality, and I think it’s going to be boring.” Again, there was a little bit of silence and, after a few moments, everybody said, “Yeah, you’re right. OK. Don’t go as dark as you did the first day.” I said, “Done.” So I won that battle, and it wasn’t even a battle. I just had to show them that this slow inching towards TNG was going to result in a show that didn’t have a distinct signature look, and that I thought it was a very bad idea. The show, even after Jonathan (West) took over, he largely maintained that look and I think he went even further than I did in some cases. He did a beautiful job, but it maintained that Batman look; not that it had anything to do with Batman. I’m just using that analogy to illustrating the difference between the two shows.