Authentic scripts from Star Trek: The Original Series are great collectibles. In addition to them being historic pieces, they make fascinating and educational reading. With regards to this latter aspect, since different drafts exist of the scripts for the produced and unproduced episodes, you can learn about the Treks that almost happened but didn’t. Furthermore, since genuine scripts are sometimes peppered with handwritten notes from the cast or crew, it’s possible to find nuggets of undocumented, inside information in them.

So, with that TEASER, let’s FADE IN on this article about the original scripts of TOS. Our ACTS here will present an overview of the types of scripts that were written and, consequently, the types that are available today. Our discussion in this STORY will also include the context in which the scripts were produced to help illustrate the relationship between the various drafts as well as some other characteristics of the scripts. However, before DOLLYING IN, we want to point out that our exposition will focus on scripts that were written in TOS’s era. The process today, and the physical appearance of the resulting scripts, are a bit different. CUT TO:

Scripts, by the Numbers

As you know, TOS had 79 episodes and two pilots, which meant that it had to have at least 80 scripts (the two-part “The Menagerie” only had one script). We use the words “at least” on purpose because, if you count the first story outlines (which are technically not scripts, but for the purposes of this article we'll include them), the first drafts, the second drafts, the final drafts, the revised final drafts and so on, you’ll quickly discover that there were hundreds of different scripts prepared for the series. At this late date, it’s difficult to know exactly how many, but there were a lot. And when you realize that Gene Roddenberry, Fred Freiberger, Bob Justman, Gene Coon, Dorothy Fontana and the rest of the production company were cranking out episodes on a weekly basis, it’s no surprise that TOS had both good and bad episodes… like most television shows and movies.

The Outline

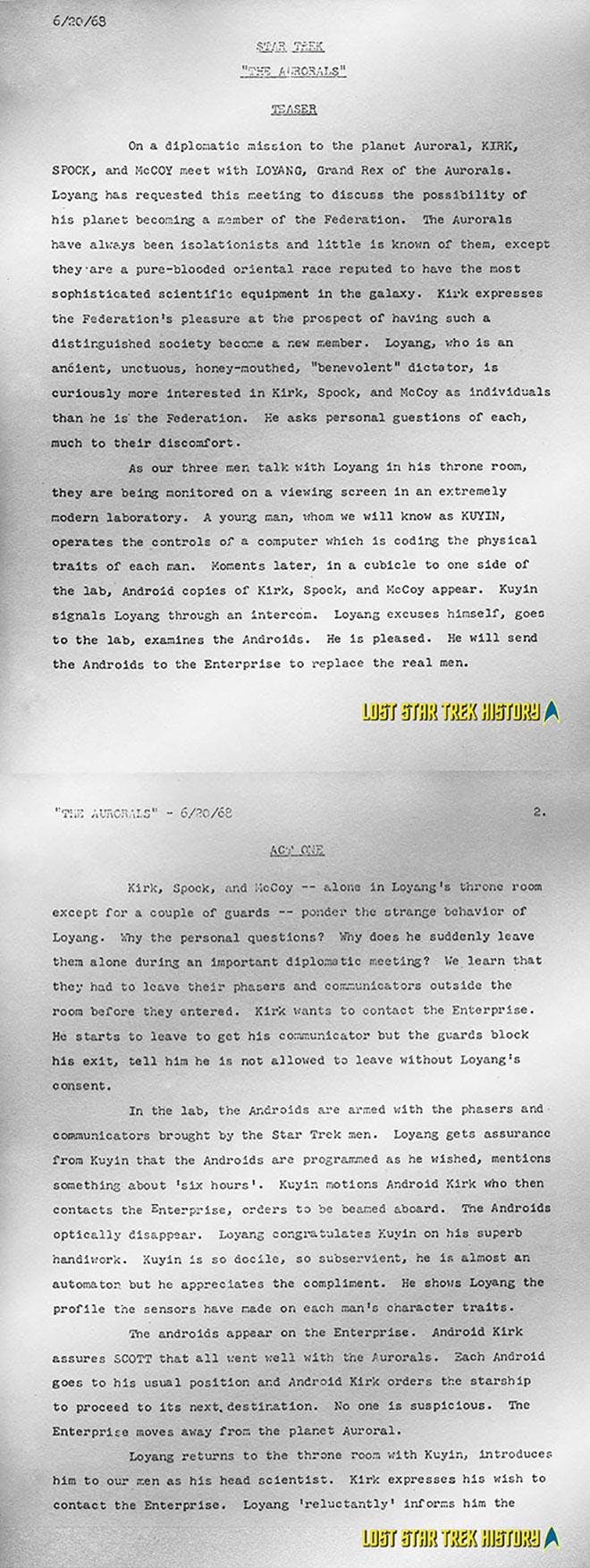

A potential episode of TOS started with an idea, of course, which was then committed to paper as a story outline. These outlines were typically short, from 2-25 pages, and were generally structured using TEASERS (the part before the opening narration designed to hook you) and ACTS (the four long parts in the middle of the episode separated by commercials). At this early stage, there were usually no scenes or dialogue in the outlines, but the stories were complete from beginning to end, and set and location changes were often indicated.

The physical form of the story outlines for TOS was pretty simple. They were typed on plain white paper or onion skin, had no formal covers and were usually stapled in the upper left-hand corner.

(Here are two pages from “The Aurorals,” an unproduced TOS story outline written by Frank Paris. Please note that we’ve joined the pages together vertically for ease of reading.)

Early Drafts

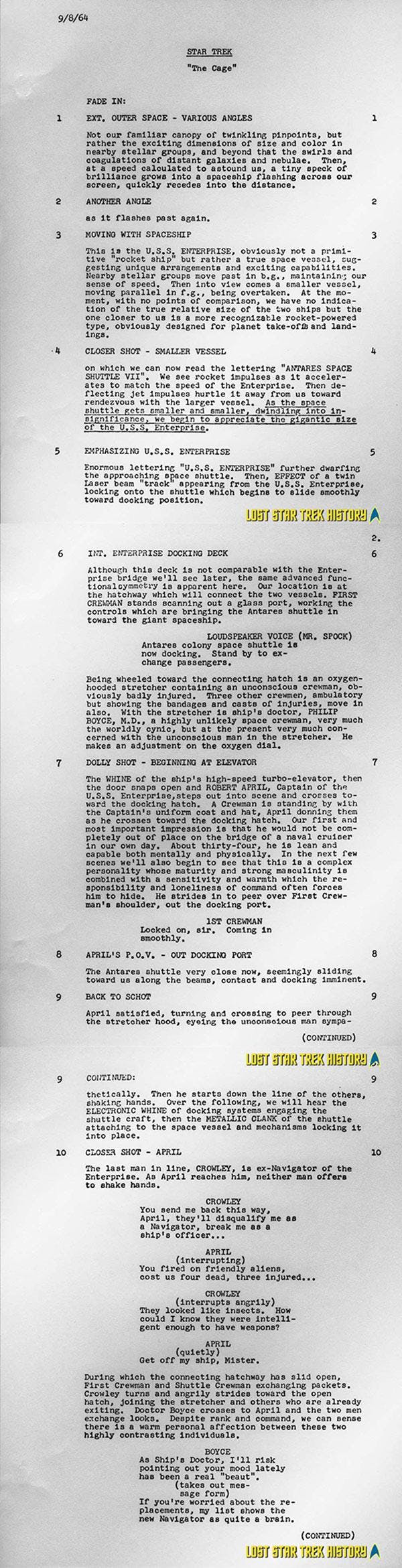

After an outline was approved, which meant that the production company, studio and network were okay with it (more on that in a moment), a writer – usually the writer of the outline, but not always – was tasked to write the first draft of the script using the outline as a guide. This first draft was usually 50-80 pages long, had cast and set lists, and scenes that were consecutively numbered, fully described and contained dialogue. The script was bound in a yellow cardstock cover using two brads. (A picture of the cover of a first draft script is presented towards the end of this article.)

Following the completion of the first draft, it was read by the principal cast members, department heads, studio and network, so that a decision could be made as to whether the basic story would work for TOS – e.g., that it would fit the format and could be done on budget – and the writer could do a good job. Everyone realized that this initial attempt was just a first shot and revisions would be necessary – no one expected it to be immediately shootable.

At this point in the process, the writer was frequently given extensive notes on the script and asked to make revisions. S/he went back to the typewriter (yep, no computers in the late 1960’s) and, if all went well, produced a final draft. It was not unheard of, however, for the writer to be asked to write a second draft, and then maybe a third draft, before proceeding to a final draft. Those second and third draft scripts, incidentally, also had yellow covers.

(The below excerpt is from the first draft script of “The Cage” written by Gene Roddenberry.)

Final Drafts

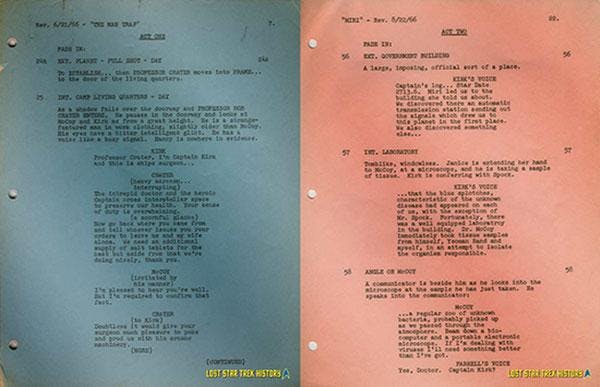

Final draft scripts weighed in at around 65 pages and were close to what the production team hoped to put before the cameras. Their format was similar to the first draft scripts, except their cover colors were gray; a few had blue covers, however, but these were the exceptions. The change of color on the cover signified that the script was locked for production, which meant that the various departments could start their serious planning and budgeting discussions. This did not mean, however, that changes weren’t made to the scripts. In fact, many were altered after they went to gray cover due to a variety of reasons, and any changes were handled through the use of colored pages to make sure that everyone could easily identify them. These colored “change pages” had dates at the top – called revision slugs – and each successive change was denoted by a different color. Their colors followed the standard scheme which started with white pages in the initial draft followed by blue, pink, yellow, green, etc. However, this scheme was not set in stone in TOS and we’ve seen exceptions to it.

(Shown below are examples of colored change pages from “The Man Trap” and “Miri.”)

We should note that when significant changes were made to the script that required a lot of change pages, the script version was incremented to the next one, e.g., a final draft became a revised final draft, a revised final draft became a 2nd revised final draft and so on. Additionally, the cover color was often changed to red.

Finally, when the last revision of the script was as “done” at it could be, the episode was ready to be shot. If all went well, this final version was completed before the first day of filming. However, there are a few instances where the script was revised while the episode was filmed. Two examples of this situation include “Mudd’s Women” and “The Enemy Within.”

We mentioned earlier that the scripts were written fast. To give you an idea of the speed at which they were, an average first draft script typically was turned into a final draft in 2-3 weeks and a final draft script (or higher revision) typically went before the cameras in 5-18 days following its completion.

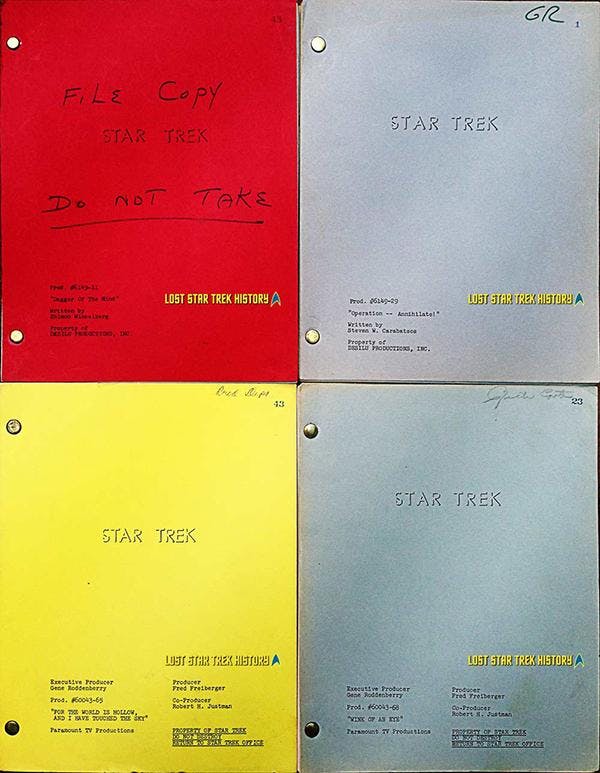

(The below shows examples of authentic, production-used scripts – a yellow first draft, two gray finals, and one red revised final. Note the information on the covers, including the large “STAR TREK” written in shadow block font and the blue machine-stamped script number in the upper right-hand corner.)

Lincoln Scripts

Before concluding this article, we want to comment on the scripts sold by the mail-order company Lincoln Enterprises. We’ve examined many that were purchased from them and can attest that quite a few were production-used; they contained colored change pages and had crew names written on their covers. Others, the majority, were reproductions, some of which were high quality and similar to the studio scripts, while others were not. The higher quality reproductions were printed on mimeograph machines and collated with two brads to mimic what was done by the studios. These copies were also done in red cover cardstock with nearly identical printing as the originals. At some point though – we believe in the mid-to-late 70’s – Lincoln discontinued the red cardstock covers and used other colored, non-cardstock paper. However, all of these Lincoln copies contained all white pages with differing revision dates at the top, a clear indicator, one of several, that the scripts were reproductions. Additionally, the scripts that Lincoln sold were not always the “shooting drafts” as they advertised – they were whatever versions they got access to.

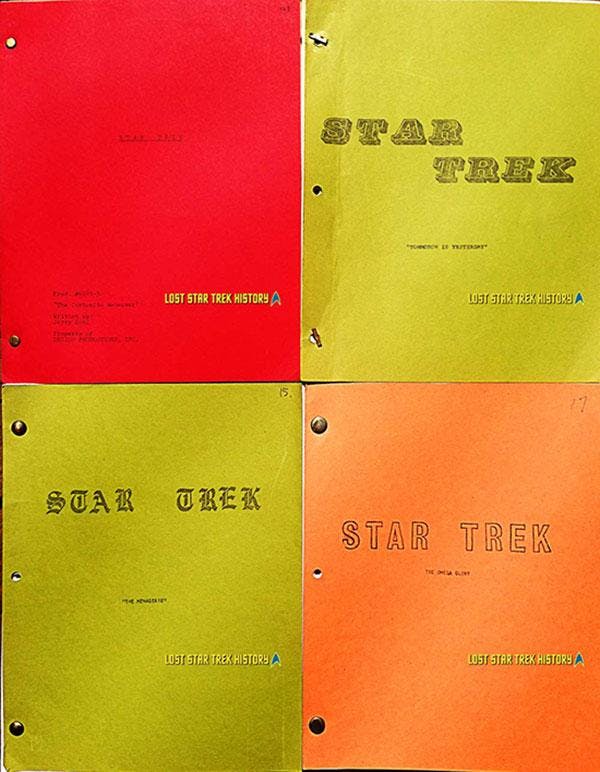

(An assortment of Lincoln Enterprises reproduction scripts, sold through the years, is shown below. Their covers are generally plain relative to the original scripts, and the words “STAR TREK” are written in a variety of different font styles. Also, the script numbers were most often written by hand, but some early ones were machine stamped in black ink.)

And with that, we’ll FADE OUT and say THE END. Until next time.

Biographical Information

David Tilotta is a professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, NC and works in the areas of chemistry and sustainable materials technology. You can email David at david.tilotta@frontier.com. Curt McAloney is an accomplished graphic artist with extensive experience in multimedia, Internet and print design. He resides in a suburb of the Twin Cities in Minnesota, and can be contacted at curt@curtsmedia.com. Together, Curt and David work on startrekhistory.com. Their Star Trek work has appeared in the Star Trek Magazine and Star Trek: The Original Series 365 by Paula M. Block with Terry J. Erdmann.