Published May 26, 2017

Shatner Talks New Book, Kirk & More

Shatner Talks New Book, Kirk & More

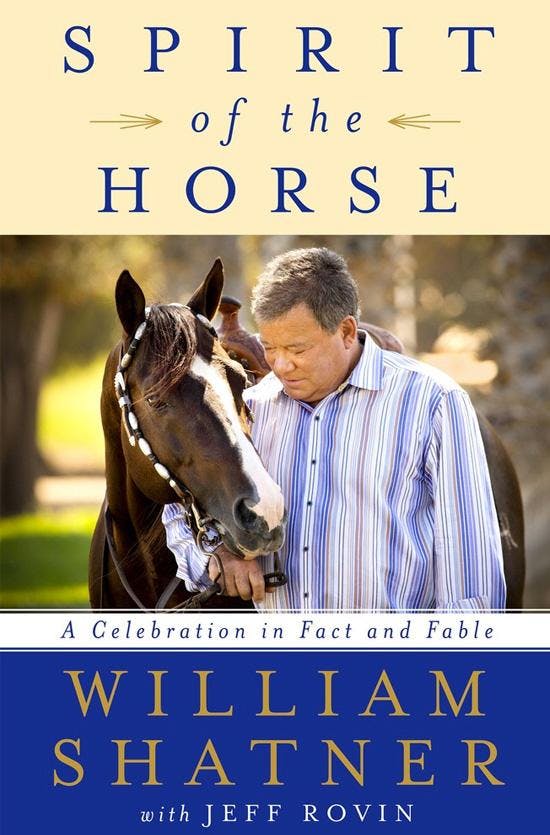

The irrepressible, unstoppable William Shatner is back in action with a flurry of projects. Star Trek’s iconic Captain Kirk has a new book, Spirt of the Horse: A Celebration in Fact and Fable, out this week from St. Martin’s Press – and we have an excerpt. In it, he shares not only his deep love of horses, but also the actual writings of literary figures ranging from Jonathan Swift to Aesop to Jack London. Shatner has also just wrapped a new film, Senior Moment, a comedy that reteams him with Christopher Lloyd, his Star Trek III: The Search for Spock nemesis. And, of course, there’s more. StarTrek.com caught up with Shatner the other day for a phone interview in which he discussed all of the above and revealed that he is really, truly ready, willing and able to play Kirk one more time…

What made now the time to write a book about your love of horses?

I've been evolving to a philosophical place over years and this personal evolution, spiritual evolution, with the horse has been taking place both inside and outside with the people that I've talked to who hold similar views and are much better at expressing it than I. I've learned from people and I've evolved in my own life.

What's your earliest recollection of experiencing the majesty and raw power of a horse?

When I was 12, I jumped on a horse, galloped around and thought about how great that is and how great a horse is, but I was just into the excitement of it. The last 30 years or more in which I've been riding, been a horseman, I always thought the horse was more, but I've only begun to really understand how much more a horse is than just being a figure of work.

It's not the old western episodes you did or Star Trek that really set you on your path to owning and breeding horses, but rather T.J. Hooker. Tell us a little about that, which you cover in detail in your book…

I was driving police cars in a barn up and down the aisles chasing the bad guy doing a T.J. Hooker. I became aware of these extraordinary horses in the stalls who were excited, but not crazed. They were also so beautiful and I learned that they were American Saddlebreds. I fell in love with American Saddlebreds. As a result of that, I became involved in Kentucky and I entered the horse world of Saddlebreds and Standardbreds in Kentucky. I became this figure of the horse.

You share excerpts of published stories about horses or those that involve horses. We particularly liked the Jonathan Swift/Gulliver's Travels story you have in there. Which were you personally happiest to share with people?

Well, they all have an interesting cast to them. There's one with an ancient old-timer, about bringing the horse into the house. The way horses were treated, at one time, horses in Arabia were part of the family. They bring them into the tent. There are such wonderfully unique stories. The Gulliver's Travels thing is wonderfully fun. It's hard to put a finger on this one's better than the other. Each is a different take on horses by these various writers whose opinion, in many cases, mimic mine.

You make a comparison in the book between horses and the Enterprise, arguing that “the starship Enterprise was a metaphor for horses of all times and every location, riding that vehicle, that means of transportation, into the sunset.” …

Well, the thesis is that horses for the last 10,000 years have been the means of conveyance and the means of taking man on the voyage of discovery. If you want to take the West, for example, Europeans came to the New Land bringing horses with them, the Spaniards down South, the English bringing their Thoroughbreds up North and gradually made their way across the continent on horseback. That’s the voyage of exploration. As a result of the horse, the intrusion... Horses had existed in North America thousands of years before, but they had gone extinct. Now, mankind Europeans brought horses back to the North American continent. They multiplied and had to fit into an environment to which they were foreign. There was intrusion into the civilization. That voyage of discovery on the horse is replicated in the voyage of discovery on the Enterprise by the means of conveyance.

You share an anecdote about Christopher Reeve. Horses are wild beasts, and there can be a price to pay for being in their presence, riding them. How hard was it back when Reeve’s accident happened to accept it, and what was it like to visit him in rehab?

I knew him vaguely. I met him a couple of times and had spoken to him. He wasn't really even an acquaintance of mine, really, but I identified with him and his accident. I knew he was in the hospital in New Jersey and I was flying to New York, so I went through the New Jersey airport, Newark, and took a car to his hospital. I, of course, called him in advance to see whether he would see me and he accepted with alacrity. I went to the hospital. It had glass doors, and I could see him waiting for me in the wheelchair and I thought, "What am I going to talk to him about?" I came into the lobby where he was sitting in the wheelchair, and he had a battery-driven motor breathing for him. He'd take a gasping breath every three words and get three words out and have to take another breath. I thought, again, “What in heaven's name am I going to say to him?” His first words were, "Talk to me about horses." We spent the whole time talking about our joy of horses.

Your worlds crossed in Star Trek Generations. What did it mean to you to ride a horse on screen in the film? And you’d pushed for that, right?

I did. The writers knew of my interest, so it was written in the stars, you know? It was great fun and Patrick (Stewart) and I joked about it and laughed a lot about it. It was great.

Let’s talk about a few other things. If you ever get to play Kirk again, what would you like to explore?

I've written about the aging of Kirk. My books are all about his life as I saw it. I was given to permission to do that, which was in defiance of everything else that Captain Kirk was. Captain Kirk got married and Captain Kirk lost his wife. He has a lot of autobiographical material in those books.

Let us ask you straight-up. How interested are you actually in playing Kirk again?

Oh, it would be incredible to do a film, which is never going to happen… to do a film of Kirk aging. I just finished a movie called Senior Moment in which I played the leading man, an older guy who has a car that he really loves and no personal relationships. He has an accident and the judge takes both his car and his driver's license away because they say he's too old to drive. He pines for his car, and eventually he meets the girl and finally gets the girl and gets the car back. That's the story: kiss the girl, get the car, and I’m the leading man. One more time. I finished Senior Moment a couple of days ago, enthralled by the idea I was given one more chance to do this, to allow all the skills that I still have and to use them and to hone them on playing this role. So, what I would love, what I wouldn't give to play Captain Kirk in the last of his age, the last of his years, doing something reminiscent of the young Kirk.

Your co-star in Senior Moment is Christopher Lloyd, Commander Kruge to your Kirk in Star Trek III. How much fun was it to work with him again, and in a comedy vs. a drama?

Hysterical. He's very funny. It was great. We had a great time together.

Last year, you were part of Star Trek Las Vegas. You hosted the official cruise. How did you enjoy all the 50th anniversary activities?

It was a lot of work. It was a lot of stuff going on. I took full advantage of the fact that it was the 50-year anniversary. I celebrated with everybody. Now, the 51st year, I'm not doing anything much, just things here and there, like Vegas this summer.

You've got your annual Hollywood Charity Horse Show coming up on June 3. Give us a preview.

We've got Nancy Wilson, the great singer, with a new group (Roadcase Royale), to entertain us. We've got a great dinner, great entertainment in the afternoon, horses and riding. And we’ve got the joy of being able to help all these kids (who benefit from the charities the event supports).

Last question… What else are you working on?

I'll be off in the next few days to do Better Late Than Never, the second season with the four guys that I worked with last year. I've got another book on aging that I've already written. It's just a matter of a re-write and compiling. I’ve got the second Zero G book (Green Space) coming out. I’ve got all kinds of documentaries and other things in the works, but those are the major things.

Read an excerpt from Spirt of the Horse: A Celebration in Fact and Fablebelow:

Horsing Around On Set

I have to tell you a story that has very little to do with horses, but has more to do with something one horse brought into my life. It’s among my most treasured memories from shooting any film or TV episode with a Western theme. We were filming an episode of Star Trek, one that involved horses. Actually, it involved a horse, and also a tiger. Strangely, the episode was not the third-season “Spectre of the Gun,” our only Western, which had no horses. In “Spectre,” crew members had been captured by an alien whose idea of fun was to drop us into a re-creation of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It was shot entirely on soundstages and was a bit of déjà vu for DeForest Kelley because a dozen years before he had costarred as Morgan Earp alongside Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas in the film Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. (I suppose it would have been doubly fitting if “Dr. McCoy” had played Doc Holliday instead of Kirk, but I digress. . . . )

The episode in question was from the first season and it was called “Shore Leave.” We shot on location at the famed Vasquez Rocks in Agua Dulce, California, with Leonard Nimoy, myself, and DeForest. One scene called for a knight on horseback to run a lance through DeForest, and another involved a tiger who was discreetly chained to the ground a few yards away.

The great thing about locations, even for TV, is that you often go to some mountain or valley or ranch or forest well outside the city. You always have to get up real early in the morning, because first you have to get there, and then you have to go to makeup. After that, if a horse is involved, there’s also the matter of getting the horse calmed and familiar with the location and ready to shoot.

While that’s going on, you have time to sit. Leonard and I were already in our Starfleet wardrobe. We had gone to the food-services truck to get something suitably rustic—an egg sandwich with onions on toasted rye bread and coffee—and then we sat there, not far from where the one horse was kept, watching the sun rise. This particular day, the sun set the sky aflame as it rose, and it was like a dream—it struck us both the same way. The dream was the skies coming to life, the privilege of doing what we were doing—it was a memory we both cherished.

Now, I love the other kinds of location moments too. You know, driving a fast car and skidding ninety feet to a stop on a cliff like we were on—which I have also done. But standing near a settled horse, with no pressure to do anything other than absorb the morning and eat the sandwich, that was magic.

The irony, of course, is that I’m a Canadian Jew, Leonardwas a Boston Jew, and we were eating something classically New York. But somehow it said “daylight and open spaces” and it was delightful, just us with the strong smell of onions and the animal now waiting patiently nearby.

Obviously, the tiger was not present that day: otherwise, the horse would never have calmed. Interestingly, when the caged cat did arrive, there was nothing restful about the location. It was electric with his ferocity.

On Westerns, or on any film with horses, things are not usually that placid.

What horses do, most immediately, is bring you humility. Whenever you think you’re doing something well on a horse, whenever you think, “Oh, I am really good,” the horse immediately, within a short while, shows you the wrongness of your conclusion. That is a lesson I remember every time I am on horseback. Every time.

Before I did Star Trek, there was a Western episode that I made for television—it may have been on Outlaws or The Big Valley, I did a lot of those shows—where the horse had to fall in front of the camera. They were going to do it the usual way, with a stunt guy looking something like me, galloping toward the camera and falling to the ground. Then they’d cut, bring the camera in, and I’d be the one to get up off the ground. That was how those things were done to prevent injury to the actor.

Being young and adventurous—or foolhardy, or maybe all three—I said, “I can do this, and make it one continuous take.”

No one raised any objections. They must have thought I knew what I was doing.

It was the evening, and they dug up the earth to make it softer, and they wet the ground down because it looks better wet—it photographs more like earth—and then there were some delays. And that’s important because when I went to do the stunt, the ground was not damp but muddy. So I rode toward the camera, pulled the horse’s head around in a flying W—a way of bringing the horse down without injury to the horse—it fell exactly as it was supposed to . . . and I didn’t get out of the way because a) the wet ground had turned muddy and was like clay; and b) my left leg ended up under the horse. The horse couldn’t get up, and it was struggling to get up. I was pinned there and struggling to get up. Even then, I was still okay. Until the horse finally did manage to get up and stepped on my leg, breaking it. Keep in mind, the cameras were still rolling.

I wanted to finish this shot so badly that when the horse got up and got away from the frame of the camera, and the director still hadn’t called cut, I rose painfully and stood there doing my dialogue, and I’m shaking with shock. Judging from the faces of the crew, everyone, including the director, thought I was giving the performance of a lifetime. In a way, I was. Method acting at its best. But as soon as the shock was over, I fell back into the mud and didn’t get up. They took me to Los Angeles County Hospital, downtown Los Angeles, to put me in a cast.

The strange or wonderful thing is, even when I was waiting in the hospital for medical care, my leg numb, I was very much aware of these amazing people working around me, as gunshot victims from gang warfare in downtown L.A. came in and out. Finally, I saw an emergency doctor; he looked like God, coming over in all his whites, handsome guy, and I thought, “Good Lord, this guy is exactly who you want to see when you come into an emergency hospital.” Yet at that same moment, lying there on the gurney, I also saw the black shoes and white socks of the policemen who were handcuffed to gunshot thugs of all stripes. I always try to look at the positives of any experience, and seeing a county hospital from the point of view of a patient was certainly that.

Getting back to the stunt, it was quite an experience to do it, have it on camera, be in such extreme pain as a broken leg, and it ending with me in a cast for a couple of weeks, not riding a horse for the rest of that episode and only doing close-ups. At the time, though, I looked at the mishap as a freak event. I know better now.

Another rewarding piece I did on horseback was the TV miniseries The Bastard, in 1978, based on the big bestseller about the Revolutionary War. I got to play one of the most famous riders this side of Lady Godiva: Paul Revere. By that time I was a pretty decent horseman and made a convincing show of riding forth to “give the alarm.”

Beyond a doubt, though, the two films I did on horseback that were most memorable to me were one I mentioned earlier, the TV movie Alexander the Great, and the feature film White Comanche, which I shot in Spain. The first one I made in 1964 as a TV pilot—quite an elaborate and expensive one, for its day. The latter was shot in 1968, when Star Trek was on hiatus.

Alexander the Great had a terrific cast. Costarring was another actor soon to take TV by storm: Adam West, TV’s Batman. Alexander, of course, was a dream part and it was a very vital, energetic production, much of it shot on locations in Southern California—locations that passed well enough for the ancient times and the sandy, sun-bedazzled hills and plains where they were taking place. I did a lot of riding in that one: rearing on a beach, galloping across a field, fighting with enemies—I loved every minute of it. I had already discovered that I was a good natural horseman, if not the world’s most adept stuntman; I was at least good enough to convince myself and the director I could do most of the action scenes. I wasn’t, not really, but I’ll get to that in a bit.

Let me state the obvious: basic horsemanship skills are important if you’re going to convince an audience that you are the person you’re playing in a Western or historical film. I’m not just talking about riding, I mean just sitting there in front of the camera. The horse isn’t in on the agenda. It wants to eat, sleep, have sex, or leave in search of one of the above. You’ve got to be able to control the animal at least that much.

For this shoot I was able to do that, and also control the horse for close-ups and the run-bys—which is when you turn away in a long shot and run by the camera. Most actors can sit on a horse in close-up, and when they start to wheel the horse away from the camera there’s an immediate cut and then a stuntman gets on that horse, or a similar horse, and rides off at a gallop so the actor is not in jeopardy on rough terrain.

You will also notice, watching films with horses, that built in to many scenes—this was certainly true in Alexander the Great—one of the other riders or some other character will come over and hold the bridle while the mounted rider is delivering lines. That’s to let the actor concentrate on dialogue without worrying that the horse is suddenly going to take a little walk. Or else you can be assured that there are one or more persons holding on to the horse off-camera, because the horse does get restless after a while and then there is always the chance, on location, that something could spook them, be it a bird or a crew member or the wind causing your cloak to flutter.

A bit of a digression, here. During the heyday of the Hollywood Westerns, in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s—which is when the genre shifted to TV—the San Fernando Valley was awash with horses trained to do Westerns. These animals knew how to stand very still while the camera was rolling and remained relatively calm around guns firing blanks and people yelling and screaming. (You don’t want them too calm or the scene will be unrealistic: a Civil War battle with horses grazing?) These horses also had to come when a rider like Gene Autry or Jimmy Wakely whistled for them, which horses do not do in real life. Before the ASPCA rightly became involved, the horse was propelled toward the whistler by a BB gun pellet fired into its rump.

That pool of horse talent had dwindled by the time I did Alexander the Great, though for all the action it was a very smooth shoot. Thinking back, I wonder if my conviction that I was Alexander and this horse was Bucephalus was somehow communicated to the animal. I like to believe it was.

My other project that year, White Comanche, was a little rockier. This one was a theatrical film shot in Spain and I played two roles: cowboy Johnny Moon and his slightly unhinged bare-chested Native American twin brother, Notah. We eventually have a High Noon showdown in town . . . charging one another on horseback and drawing at full gallop. I won.

Now, this shoot was even further along in that period I was just discussing, when Hollywood had stopped making traditional Westerns. By 1969 they were hardly making any kind of Westerns at all. This was the era of the antiheroic films like Easy Rider—but in Spain and Italy, the so-called spaghetti Westerns were suddenly very popular. That’s why Clint Eastwood went there, Eli Wallach, Lee Van Cleef, and many others who had worked in the Western genre. The demand for Hollywood actors who had international recognition was great.

So off I went, too. It may not have been a brilliant project but sometimes actors do things because they get to spend time in another country. I know that’s why some Hollywood actors went to Japan around this time to shoot Godzilla movies, of all things; they got paid to work in Tokyo.

That entire film was fun. I had two horses, though not for the reasons you might expect; they weren’t for the brothers but to perform different functions on-screen. This is not uncommon. Charlton Heston had two identical stallions for his 1961 epic El Cid, one for moving easily among other horses and actors, the other for charging sure-footed on the beach and icy mountain passes. (Heston once remarked, “You haven’t lived until you’ve jumped on a saddle, in stiff chain mail, at five in the morning on a frozen hilltop.”) In fact, Chuck used to tell a story about the wrangler bringing the wrong horse for the scene in which El Cid was supposed to be propped, dead, in the saddle to lead the climactic charge. If you watch the film you can see that this horse just wanted to run, not parade to the battlefield. It turns one way, then another, and you can also see Chuck heroically preventing it from doing so with just his legs . . . since he was supposed to be dead. It’s a masterful job, one that most viewers probably wouldn’t notice. Which is the point.

White Comanche was shot, fittingly, at the soundstages and back lot of the former Bronston Productions, where El Cid had been made. Like Heston, I had a horse they named El Nervioso as the long-distance horse, the horse I would ride at a gallop, and then they had the close-up horse, El Tranquilo, who would be calm when the clapboard clacked in his face and I had to wheel the horse away and ride off into the sunset.

As it turned out, before too long the horses had to trade roles, because after my guidance and ability to control him, El Nervioso gradually calmed down, became very tranquil. Meanwhile, El Tranquilo was getting real nervous about people jumping up and down in front of the camera, and he became El Nervioso. So then we had to switch the horses.

Of all of the horse stuff that I did over my career, that was the most challenging and also the most fun. I enjoyed “reading” the horses, if you will, knowing just when it was time to swap one for the other.

This would probably be a good time to mention another challenge on the shoot: I rode these two horses bareback, which added to the danger. I learned to do this under the aegis of Glenn Randall, Jr., one of those gentlemen who, like Yakima Canutt (more on that legend later), was born to do what he did. His father had been a renowned rodeo rider and movie horseman before him. Glenn Jr. went on to become a masterly stunt coordinator for films that didn’t have any horses, like The Towering Inferno and E.T., but back then he was still in the original family business of horses.

With Glenn’s help I became competent enough but, obviously, as I said, riding bareback adds another level of danger to anything beyond a trot. And it was very stupid of me to ride El Nervioso that way, across a field, because with some frequency horses break their legs stepping in a gopher hole. And everybody knew that, including me. I had the arrogance going in—but as the days passed, and I became aware of just how many things could have gone wrong, I was forced to reevaluate my skill level. I was also a little more mindful of the risks than I’d been in other films. As on the plains of the American West, there are many potential life-ending scenarios that come from riding a horse full-out on a prairie. I would take time to walk whatever path I was supposed to follow, looking for pitfalls.

Glenn also showed me how to do a stunt that I really loved. It was a trick of rolling backward off the horse as the horse was cantering along, as if I’d been shot. The idea was I’d fall backward, land on my feet, and then fall on the ground—secretly fine, thus luring the enemy in. I pulled it off, though I can only imagine what these Spanish guys who knew and loved horses really thought of me, so eager and cocksure. But then, as I said about Alexander the Great, I didn’t want a stuntman having to double for me in a single scene. I wanted to do it all. And that’s what I did.

Thanks to Glenn and whatever guardian angel was watching over me, nothing happened, I never got hurt on that shoot, but as I look back on it now I think, “How could you have done that?”

There is one more story I’d like to share, one that has nothing to do with riding but with the larger theme of this book, the spiritual magic of the horse.

In 2002, I was directing a movie called Groom Lake, about a woman’s search for extraterrestrial life. We were shooting in Arizona, right near the border between Mexico and Arizona. When we were shooting at night, every so often the lights would pick up some individuals coming over a rise. And we were told that it was dangerous because that location was near a known border crossing. The “coyotes,” the leaders of the border crossers, were taking people across in groups and it could be risky for us since we were there with cameras possibly photographing people who absolutely did not want to be discovered.

In addition, not because we were there, but as a matter of course, border guards would often turn up, walking in the dark, and would come into the frame, and we would have to stop shooting. You wouldn’t think shooting on location, in your own land, could be so difficult and treacherous, but there you are.

Eventually I made friends with some of the border guards, and they invited me to come and patrol the border. That’s the kind of experience you don’t pass up, and when I wasn’t shooting at night, and my preparations for the next day were done, I went with them. My wife Elizabeth was with me.

She and I got into a car and drove to the border to meet these two border guards, and one of them said, “We know both of you are interested in horses, and we have horses here that we took from the ‘coyotes.’” So Elizabeth and I got on the two horses and the border guards were on foot; Elizabeth is an expert rider, having trained horses for most of her life. They handed us night-vision goggles so that we could see— albeit in that eerie, luminous shade of green—and we went into the brush, which had a great deal of cactus. The border guards knew the cactus, the horses knew the cactus because they were desert horses, and we got to that rise where we’d been seeing people all through the shoot. It was a swell in the earth, and the border guards whispered, “The border is right over there, let’s stay here for a moment.”

We all stood silently under the night sky, practically no light at all, just starlight. And the horses too stood, immobile.

And I whispered, “What exactly are we waiting for?”

And the border guard said, “These horses were mistreated by the guys running the people. They hated the people that owned them. When we confiscated these animals, we realized that their ears would move, that they would look in the direction that the ‘coyotes’ were coming, were bringing people across the border, because they were so apprehensive about their former owners that they would immediately be alerted. And only they could hear and smell what the human beings, the rest of us, could not.”

So now we’re in that situation, and suddenly both horses swivel and point in the same direction. And the guards start running off into the dark, and we’re on the horses and we’re riding to keep up—because we did not want to be there unprotected. We’re racing past cactus, over brush, and we can’t even see who we’re pursuing—even though we can “see” in the dark! And suddenly we come upon a group of twenty-five people huddled, getting ready to be moved on into the United States. The guards said, “Now you all sit there and put your hands above your head.” And they arrested the guide. The horses did not relax, but we comforted them, assured them that all was well. The sensitivity of these horses was both impressive . . . and very, very moving.

But there’s a coda. As Elizabeth and I are sitting on these horses, looking at these poor people who are trying to come to America, we’ve got the night goggles on and now I can see this one particular guy, a young Mexican fellow, and he looks up at me and he says with a curious sense of awe and disbelief: “Captain Kirk.”

Copyright - Copyright © 2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books.

Spirit of the Horse is available this week. Go to amazon.com to purchase it. And additional details about the Hollywood Charity Horse Show can be beamed up at www.horseshow.org.