Published Nov 21, 2015

Interview: Trek IV's Punk on the Bus

Interview: Trek IV's Punk on the Bus

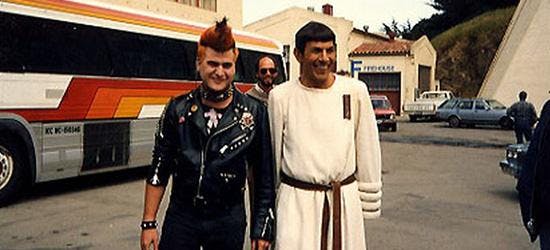

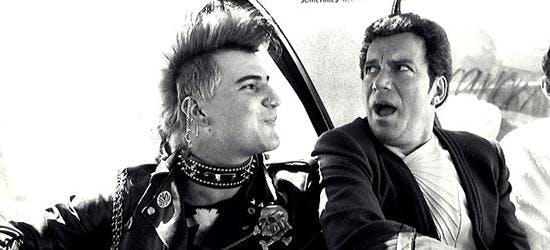

What’s the common denominator between Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Star Trek: IV: The Voyage Home, Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, the punk on the bus in The Voyage Home, the Muppets, Gremlins, and also the Lifetime television movie Jim Henson’s Turkey Hollow? The answer is Kirk Thatcher. Thatcher worked on Wrath of Khan and Search for Spock during his early days at Industrial Light and Magic. It’s also where he worked on Gremlins and Return of the Jedi. He served as Leonard Nimoy’s personal assistant on The Voyage Home, eventually receiving screen credit as associate producer. He also, for that film, played the punk on the bus and even co-wrote the song “I Hate You.” Oh, and he provided the voice of the Vulcan computer. As for the Muppets, he learned puppeteering from the best: Jim Henson, and went on to write, produce and/or direct several Muppet projects, including It’s a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie, The Muppets’ Wizard of Oz and now Jim Henson’s Turkey Hollow, which will air tonight.

The family film is based on an unproduced Thanksgiving special Henson and his writing partner Jerry Juhl first envisioned back in 1968. The tale centers on a newly divorced father and his kids, who venture out to the country to spend time with their eccentric Aunt Cly (Mary Steenburgen) on her farm, only to learn that the area’s celebrated mythical monster, the Howling Hoodoo, may not be all that mythical. Then, while searching for the Howling Hoodoo in the forest just beyond Aunt Cly’s farm, the family comes across four other unusual, furry and music-loving creatures. StarTrek.com caught up with Thatcher for a detailed conversation in which he discussed his career, the passing of his friend and mentor, Nimoy, and Turkey Hollow. Here’s what he had to say:

Let’s start with Star Trek. How did you first connect with the franchise?

I had been at UCLA animation, learning about computers. I got the job at ILM when I’d just turned 19. I was actually 18 when I got it and 19 when I started. I worked there for about three years. Then I worked on Gremlins with Chris Walas, and I realized that computers were going to take over the FX industry, even early on. Lucas had the early stages of Pixar. Even John Lassiter was there, and they were doing these simple animated shorts. Then, on Star Trek, they’d done the Genesis thing. But I went back to UCLA to study computer animation, and while I was there someone came through the animation department to say they were looking for an assistant to Leonard Nimoy on Star Trek IV. But you had to know special effects. So I was tailor-made for the job. I went and met Leonard, and I knew he’d met a couple of other guys. But I’d literally just stopped working at ILM six or eight months earlier. So I knew everyone. I knew the processes they used. And I knew the political environment. That’s not why they hired me, but I knew who to talk to if there was a problem.

And you and Nimoy hit it off?

We did. He was such a charming person. Avuncular is the word I use. He was like an uncle. So we went to lunch and he asked me some questions, and we talked about Star Trek and Star Wars, and what I liked about both of them. Had I seen Star Trek? I was a closet Trekkie. I’d grown up watching it and loved it. One of the funny stories was that when Star Trek IV screened my parents met Leonard, and they said, “Oh, this is such a big thing for our son. He had a poster of you and Captain Kirk above his bed.” I’d never told Leonard that, so I was mortified, of course. I was glad he found out at the screening and not before I got the job. Sorry if I’m going out of sequence. I worked on II and III because I was at ILM, in the creature shop. I helped build Chekov’s ear and the Ceti eels. In fact, somewhere, there’s a shot of me helping animate worms that came out of the bacteria in Spock’s coffin. And I puppeteered the Klingon dog, too, the one that sat at Christopher Lloyd’s feet. So I was under a chair on the Klingon Bird of Prey, animated that dog for a lot of days, though I don’t think I got a credit.

So you met Nimoy, but didn’t really interact with him on Search for Spock? Everything from working with him to being the punk on the bus came together on IV…

Right. It was on IV that I got to know him. I started as his assistant and then, about halfway through, he said, “I’d like to make you associate director,” but there was no such term. I couldn’t be a first assistant director because that’s an actual job. So he said, “Would you be OK with associate producer?” I said, “Of course. Thank you so much.” Then the punk scene just came about because I said to Leonard, “Hey, there’s this scene in the movie. Can I play the punk.” I’d been in a punk band and I’d had a shorter version of the Mohawk before. He thought about it for a week to 10 days and then said, “Yes.” I said, “You won’t regret this.” I went and got my hair done and gathered the outfit.

And how was the “I Hate You” bit done?

It was done dry. There was no music playing because they wanted to record the dialogue with Leonard and William Shatner. So I was just bopping along to a metronome in my head. When it came time to put a song in there, Paramount had their music publishing division. The bands they were thinking of weren’t really punk bands. They were more new wave, more like Duran Duran. This was supposed to be angry punk music. I told Leonard that I could bang out a song in a couple of hours that would be an appropriate punk song. And he said, “Have at it.” So I did it. And the sound effects editor/designer, Mark Mangini, had become friends. We worked together on Gremlins. So he turned it into a guitar riff. And that’s how “I Hate You” came about.

What else did you come up with for The VoyageHome?

I came up with passing out on the boom box. I came up with Scotty talking to the mouse. That was a gag I wrote. I wrote the dialogue at the beginning of the movie, when Spock is at the computer and the computer is asking him all these questions and he’s answering. They recorded my voice as a temp track, just so Leonard had something to react to when we were filming. Ultimately, they just said, “Hey, we’re going to use it, but we’re not going to give you a credit because you’d be in the credits like five times if we did.” I said, “That’s OK. I’m just honored that you used it,” not only the questions, but my voice. I also got to work with the guys designing the aliens. I got to help redesign the Klingon foreheads, because they thought they looked like a waffle iron on someone’s head. I said, “Let’s go back to something a little more subtle.” There’s no wrong Klingon forehead, but I got to art direct what I thought they should look more like. Leonard let me be involved in a lot of that kind of thing, because he was so involved in the story and making the characters work. It was a huge show of trust by Leonard, and I’ll be forever grateful.

And it was a great learning lesson for me. At that point in my life, what made a movie for me was art direction and special effects and production design, and not will the boy get the girl or will the friends make up? It was a great lesson for me about the importance of the story. We’d talk about directing. Leonard would say, “All this technical stuff, you can rely on other people who know much more about it than you do. But the one thing you have to know is your story and why people should care. What’s going to make them care about the characters, whatever they are, whether it’s live-action or animation or puppets. Why do we care about them?” I think that’s why several of his movies, particularly Star Trek IV and Three Men and a Baby, were so successful. You cared about the characters and what they went through, and you went on the ride with them. Thanks to Leonard and Harve Bennett and Nick Meyer, all of the characters on Star Trek IV came through. They told a story that made sense and was fun, but it was a story about this group of friends going through this experience, with one of the friends having just come back from the dead.

You and Nimoy stayed in touch over the years. And, a year or two before he passed away, he tweeted a shot of the two of you having lunch together. Was that the last time you saw him? And what do you remember of the day?

We had stayed close. We had lunch a couple of times a year probably through the late 90s. Then I was off doing movies and it became once a year and then once every couple of years. He sort of retired from the film business. But we’d go to a deli near where he lived, and we’d talk about life and show business. Again, the uncle analogy is really true. He’d say, “Who are you dating? What do you really want?” I remember, in my early 30s, saying, “Well, I have a house now and I’m looking to meet someone.” He said, “That’s good. That’s good. That’s important. You’re settling down and finding your way.” Later, when he retired, I said, “So wait, you’re going to retire and just take pictures of naked women in your garage?” I said, “You set up my goals. I want to work in the film business, retire on a high note and then just take pictures of naked women at my house.” He laughed. He had a great sense of humor and we could joke back and forth. Leonard was such a wonderful guy that you could not not be friends with him if he wanted to be friends with you. Spock was this cold, unfeeling, logical character, but in real life Leonard was this warm, funny, curious guy who actually cared about people and not just the work.

And that photo was from the last time I saw him. I hadn’t seen him in probably four years. Then one day I was driving and I got an email or a text from Leonard. It said, “Hey, what are you doing?” I said I’m driving through the canyon, going to the beach. He was like, “Sounds good. Let’s have lunch or dinner.” So he sort of started it. He told me he had COPD and he said there wasn’t a great prognosis. We had lunch at his place; he didn’t want to go out. We talked about his kids and his grandkids and his nieces and nephews. We talked about family and what I’d been doing and just life in general. He said he had to be on oxygen once in a while. He didn’t dwell on (his illness), but I had the feeling it could be the last time I’d see him. If you see the photo, I look a little melancholy. And I think that’s how I was feeling, like, “Is this the last picture I’m going to have with him?” He lived another year and change. But that lunch, which was about two hours… I think it was his way of saying goodbye without actually saying goodbye. And we texted or emailed for the following year, until he passed away.

Let’s talk about your current project, Jim Henson’s Turkey Hollow. How natural was it, given your connection to Henson and your previous Muppet work, that you directed Turkey Hollow?

Well, I’d like to think it was natural, but there’s no guarantee about anything in this business. And I’m a freelancer, so that’s doubly the case. So I was certainly honored when Lisa Henson and Hallie, the development exec, called me and said, “Hey, we found this project that was sort of buried.” They showed me the pictures and showed me the outline, which was 12 to 15 pages, and said, “Read it and tell us if you’d be interested in maybe writing and directing it.” I said, “Well, yeah,” pretty much sight unseen. Then, knowing the history, I was interested. And when I read the outline, I just fell in love with it. It had this sweetness and whimsy. But, yeah, they called me – and I was flattered that I was the first person they thought of for it.

Henson had even made puppets for this project back in the day, though the ones we see in the movie were done by the Henson Creature Shop. How much fun did you have making this movie and directing the creatures?

They found the puppets in a box, in a bag. There are picture of me with them. They were much simpler than we ended up making. They were more alien, in a weird way, in that one looked like a weird, furry octopus. One had this insanely long neck. What we tried to do was distill them down. There were originally five, but we went with four just because of time and budget constraints. My concern was I didn’t want people to think this is a kids’ special. I didn’t want them to think it’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. I wanted this to be a family film that’s somewhere between E.T. and Gremlins, if the Gremlins never became nasty. And I wanted our creatures not to be as cute as Mogwai and not as creepy as E.T. I think we really found that balance. I wanted it to be a charming movie where the parents watching it wouldn’t roll their eyes. There was a comic that was done in the past couple of years and that was based almost strictly on the outline that Jim and Jerry had written. So it was a little broader and the puppets were more along the lines of a kids’ special. This is more of the family film I was after, and even “family film” is a dreaded term now. Whatever E.T. is, that’s what I wanted this to be like.

And I loved directing the puppets. Coming from an extensive Muppet background, I speak to these puppets as if they’re the character. Kermit, to me, is Kermit. On this I’d talk to the characters as characters, but if something like an eye line was off, I’d say to the puppeteer, “Hey, Robbie, could you just cheat your eye line a bit?” But if I was dealing with the performance? I’d say, “Burble… look more shocked or look happier.” So I kind of split the difference. But they definitely do become real. The other thing that I used as a touchstone for both the actors and the puppeteers was I said, “I want them to feel like slightly unruly golden retrievers.” I came up with these big fluffy tails for them, which were not in the original designs. The tales let us show them moving through the forest, because we didn’t have time to dig trenches or create these complicated radio-controlled creatures, and I didn’t want to use CG. So, with a dog, all you see is the tail up like a flag. A tail tells you a lot about a creature’s mood even if you can’t see their face. The tails – these big, happy, wagging tails -- also make them more endearing. It makes you just want to hang out with them or, at least – I hope – want to watch them for a couple of hours.

Looking at your career, do you feel a bit like a kid in a candy shop?

Kid in a candy store… You know, with the creature work I’ve done, it’s just so normal to me. It’s what I do. But I realize I’m a guy living in rarified air. So it seems normal to me, but I realize that for most people it’s like getting to be Willy Wonka. Though, I have to say, George Lucas and Jim Henson and Leonard Nimoy, they were really Willy Wonkas in their own right. Getting to work with and apprentice with them, it feels like it’s been a very natural progression for me.