Published Sep 8, 2014

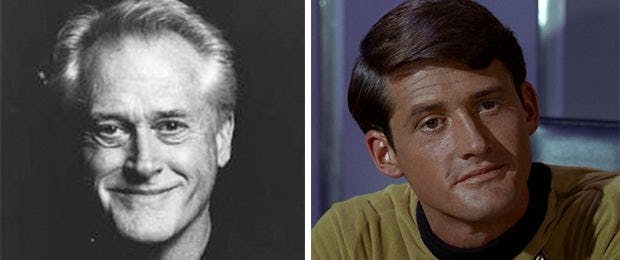

Catching Up With Trek's Lt. Kevin Riley... Bruce Hyde

Catching Up With Trek's Lt. Kevin Riley... Bruce Hyde

Bruce Hyde didn’t act very much – really, just some stage work and a handful of TV guest spots over a few years back in the 1960s, among them two episodes of Star Trek: The Original Series. He played Lt. Kevin Riley in “The Naked Time” and “The Conscience of the King,” thus making his mark on the franchise. Once a convention regular, Riley doesn’t turn up at them very often these days. Nor, for that matter, does he grant terribly many interviews. For all those reasons and more, StarTrek.com was thrilled when he agreed to sit down with us for an interview just moments before his appearance on stage at last month’s Official Star Trek Convention in Las Vegas. Despite a raspy voice (which is explained during the conversation below), Hyde was eager to chat and full of great anecdotes about his Treks, career and life today. Here’s what he had to say.

You shot your two episodes of Star Trek 48 years ago. First, how surreal is it that they were so long ago? And is it more or less surreal that people are still eager to hear about your experiences all this time later?

HYDE: I’m honored to have my little toe in pop culture history. I only made a living as an actor for six or seven years, and Star Trek, these two episodes, were about three weeks of work. So I’m dumbfounded. I think it’s a good thing. Star Trek is certainly a good thing. I have the sense that Gene Roddenberry had a vision, a kind of “We come in peace” vision of the world. Even if these people at the convention today don’t know that – because I’m not sure how many people talk about Star Trek at that level – it’s there. That vision was embedded in this whole Star Trek phenomenon. There is, in a world of chaos and separation, this vision of a group of people who go out into space, unified in their purpose. And that’s great. As for me? I thank people for even remembering me. Everyone I’ve seen today, I’ve said, “Thank you.” I just did those two episodes, so to be included in an event like this, it’s an honor. It strange that anything survives this long, but that Star Trek has I think is a tribute to Gene Roddenberry’s genius.

How did you land the role of Riley?

HYDE: I was an actor living in New York and I had an agent at one of the big agencies. I did a screen test for Desilu Studios and was cast in a pilot they had going. And, as part of the deal to keep me available, in case the pilot sold, they could use me in a few episodes of whatever else they had going at the time. The two shows they had were Mission: Impossible and Star Trek. So, as part of that deal they cast me in the two Trek episodes. Originally, they were not supposed to be the same character, but they called me Riley in both.

What do you remember most about shooting the episodes?

HYDE: The singing part is what is still most vivid to me. I feel a certain affinity to that song, “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen.” It was, for a long time, for me like “Over the Rainbow” was to Judy Garland. I used to be asked to sing that song at every convention I attended. I don’t know if I’ll try it today. Right now, because of my voice, I sound a little like Louis Armstrong or Tom Waits.

The director of your first episode, “The Naked Time,” was Marc Daniels. He’d directed years of I Love Lucy and, pre-Trek, he had directed you in a play that you toured in for a while, right?

HYDE: Yes. He was very much a father figure to me and I loved working with him. I’d never done much film or television work and I was very uncomfortable, and I just remember Marc being so kind and so supportive to me. There’s a photo of him with me when I’m in the engine room after I’ve taken things over. His hands are on my shoulders, and I know exactly what that moment was. He was grabbing me by the shoulders, loosening me up and saying, “Relax.” So that’s what I remember most, being uncomfortable because I was so new to it and having this wonderful, generous man be my director.

You mentioned earlier that you dropped out of the acting game after six or seven years. Why?

HYDE: The last thing I did professionally was to act and sing in Hair, in a production of the show in San Francisco. I did that for a year and I got very active in imbibing psychedelic drugs. After a year of playing a hippie on stage I decided that I wanted to stay in San Francisco and play one for real. So I dropped out of acting and I lived in San Francisco for 10 years. I was a housepainter most of the time and then I became a personnel manager for a large house-painting company. And, really, I went off to find God, to find a lot of “self.” San Francisco was full of truth-seekers in those days and I really wanted to find myself. I found some brilliant teachers, but really, I was pretty f—ked up, and I’m really fortunate to have survived all that. A lot of people didn’t. I needed a lot of work, and I got a lot of work. And, right now, I can tell you, I have the best life. I’m married to a wonderful woman. We live in a house on the Mississippi River, overlooking the river. I have a wonderful job. Being a tenured, full professor at a university is one of the most-secure, fulfilling, flexible jobs you can have. I love my life. It couldn’t have turned out better.

You did conventions very early on, when they were first really happening. What was that like for you?

HYDE: It was very bizarre. At my first one, one of the questions during the trivia contest was, “What was the poison that Kevin Riley drank in the milk in the episode ‘The Conscience of the King?’” I thought, “Oh my God, this is so strange.” Sometime after that, someone else located me and asked me to do another convention. The ones I was doing were mostly small fan-run events. At the time I didn’t have a lot to say about what it was like working with William Shatner because it was three weeks work. And, at the time, I was living in San Francisco and writing songs. So I would take my guitar to these conventions. I’d written some good songs, and so I’d perform them for the fans. It was something different for everyone. So I’d get invited to another one and another one and another one. I don’t do very many of them now, but I still enjoy them, still feel so privileged to have them in my life, and it’s remarkable how different being a convention guest is from being a communications professor.

Which brings us to the fact that you are indeed a communications professor. Can you give everyone a sense of what your courses are like?

HYDE: I am in my 25th year as a tenured professor at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. I teach communication studies, small-group communication, interpersonal communication, and I am also writing a book at the moment with a colleague. The book is about a man named Werner Erhard, who, in the 1970s started a program called est, the current iteration of which is Landmark. He is the person who has most influenced my life in every way, and my colleague and I are writing a book showing how Werner’s thinking is consistent with the thinking of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. And it’s a fascinating subject and challenge. We just had a phone conversation with Werner yesterday, and to be engaged at this level with the man who has most influenced my life and who I consider to be the only real genius I have ever known, is such a treat.

You’re writing, you’re teaching and you’re a cancer survivor…

HYDE: I had throat cancer in 2010. So, for me, talking is a little bit more work than it used to be, but I just passed my fourth year of being cancer-free and after one more year, my visits to the Mayo Clinic will be reduced to an annual checkup. They cut a lot of stuff. They cut my throat and a lot of muscles, but that just means the students need to listen more carefully. Since I’m teaching communication, though, that’s not a bad thing. The other thing that is a challenge as a teacher is that each year the students are a little more immersed in their technology. They’re a little less focused and they live in a world of constant distraction. They don’t ever have to be alone with themselves. They can always go somewhere else. My sense is that’s affecting their way of being in life and, specifically, in the classroom.

So that’s an interesting challenge. I tell them, “Look, I’m not anti-technology. It’s a great thing. But you are digital natives. You are immersed in technology throughout your lives and, in this class, I’m teaching you face-to-face communication. I’m going to give you a non-digital experience in here.” So, again, I’m not saying it’s bad, or right or wrong, but in my class it’s non-digital and we look each other in the eye, and I ask them to think about, “Where are we going? And if you’re not able to look into somebody else’s eyes, are we – are you – losing something?” It’s a question for them to explore, and I think that’s important.